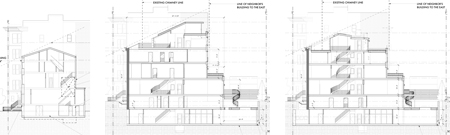

In an April 19 public hearing, the Landmarks Preservation Commission asked 404 West 20th Street’s new owner Ajoy Kapoor to return with a more appropriate proposal for altering it. Just released, the revised proposal will go before a public meeting of the Commission on Tuesday. The new design takes a little off the top and still appears to require virtual demolition of all but the façade of the house, the oldest in the Chelsea Historic District. Excerpted from the updated presentation by Kapoor’s architect William Suk and aligned for comparison are, left-to-right, the section of the existing house, the earlier proposal and the current proposal. The new building would still be well over twice the actual area of the approximately 4,000 square foot existing house, thanks in large part to a huge new basement excavation which would in itself make retention of the existing house difficult. In ArchiTakes’ opinion, both the form and substance of the existing house are lost in its proposed replacement.

A plaque long mounted to the front of 404 West 20th Street is missing since the house was bought last year by Kapoor. The plaque is thought to have been installed shortly after the 1970 landmark designation of the Chelsea Historic District in which the house stands. The building’s historic distinction and rare surviving wood frame complicate Kapoor’s plans, which depend heavily on Suk’s assurances to the Commission that the house is structurally deficient. At the April 19th hearing and in Suk’s presentation materials, these weren’t backed up with an independent engineer’s report, and his claims mainly pointed to the kind of construction technology and deformation normally found in old frame houses. His broad statement that “this whole house is falling apart” was not questioned by the commissioners. “I wouldn’t put a kid to bed in that house,” one commissioner said. “It’s patently unsafe not to mention the building is clearly falling apart.” Another commissioner didn’t call the house a threat to children but dishearteningly seemed to take condemnation as a foregone conclusion and spoke of a possible solution that would “give some deference at least to that original structure and record some memory of it as best can be done.” Why wouldn’t the Landmarks Preservation Commission just preserve the landmark that’s standing there? Many experts might say that in leaning only two inches to one side after 186 years it exhibits stability rather than the instability Suk makes of it. Shouldn’t the spatial ambition of Kapoor’s proposal inspire a little more scrutiny of his suggestions that preserving the existing house is a lost cause?

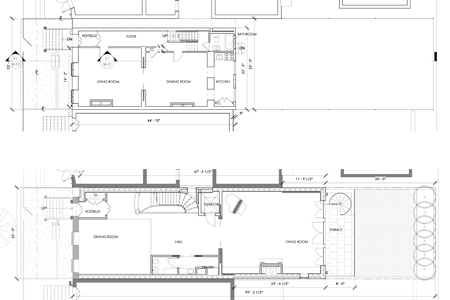

404’s existing (top) and proposed (bottom) main floor plans from William Suk’s latest presentation are aligned for comparison above. They continue to make obvious the disappearance of the old house save for its facade. The historic side alley seen just above the existing plan is subsumed in the much larger proposal, which also expands into the rear yard. Despite this apparent removal of the existing house, the project was described on the calendar of the Commission’s website as an application “to construct additions and excavate the rear yard,” and introduced as such in the public hearing. Although Community Board 4’s advisory letter to the Commission and several public speakers in the public hearing criticized the house’s proposed virtual replacement, Chair Srinavasan asked Kapoor’s counsel, Valerie Campbell, “How much of the building will be retained?” The Chair did not challenge Campbell’s answer that, “in trying to stabilize the building and to bring it up to code, there is a significant amount of work that has to be done to the building.” Campbell otherwise spoke in the hearing of measures needed to ensure the house’s “preservation” or “longevity.” She is described on the website of her firm, Kramer Levin, as a former General Counsel of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

In a 1965 photo, 404’s brick front is temporarily painted, while sunlight picks out its contrasting wood clapboard siding. A tiny alley exposes this evidence of the house’s frame construction, along with its historic pitched roof. A young Lesley Doyel stands in front. Her family bought the house that year after renting an apartment in it since 1952. Ms. Doyel is a longtime community activist and founder of the advocacy group, Save Chelsea. She and her husband Nick Fritsch sold the house to Ajoy Kapoor last year, having reason to be confident that its location in the Chelsea Historic District assured its preservation. According to the website of the Landmarks Preservation Commission: “If your building is in a historic district, it’s regulated the same way as an individual landmark.”

404’s wood siding has been a staple of Chelsea walking tours for decades. “I remember being shown the side of that house in an architecture class way back in my NYU days,” said Wendy Solem, a neighbor who called the house’s possible fate “truly heartbreaking.” Joyce Gold, who runs Joyce Gold History Tours of New York, said she has been leading groups to the house for 35 years and that it lets her “raise the subject of when wood could be used, and when it couldn’t.” In response to major fires, construction of wood houses was progressively banned in zones extending northward as the city grew. By 1849 the ban reached 32nd Street. Surviving wood-frame houses such as this one are very rare in Manhattan, but this only scratches the surface of 404’s significance to those who live in and visit the city and have an interest in exploring its roots.

Images from the latest submission compare the existing alley (left) with its still-proposed infill (right), now with its recessed face in wood siding. The alley would be commemorated with a bizarre and inexplicable shallow clapboard niche imitative of the existing historic side wall. The historic side wall itself would be lost along with views of the house’s period pitched roof. Current zoning doesn’t allow creation of side yards less than eight feet wide, but pre-existing ones like 404’s two-foot seven-inch alley are grandfathered. The alley can legally remain provided no addition to the house is built within eight feet of its side property line. Filling in the alley would eliminate this restriction on additions, while preserving it would still allow a substantial rear extension and preserve the visibility of the house’s pitched roof seen through the alley, not to mention views of its historic wood siding. At one point in the public hearing, the Commission mistook the width of the building lot for twenty rather than twenty-five feet, and the width of the allowed addition zone — if the alley were retained — for twelve rather than seventeen feet. This appeared to generate sympathy for Kapoor’s proposal to fill in the side yard. The Chair and commissioners were not corrected by William Suk, or Kapoor’s counsel, Valerie Campbell.

The Commission didn’t voice recognition of the significance of the narrow alleyway itself. Chair Srinavasan dismissed it as a “quirk,” saying “I can’t get all romantic about that side yard” and stating that she could “support” filling it in. Yet romance has little to do with it. Research uncovers plenty of justification for preserving it as a once-pervasive but now unique feature of the Chelsea Historic District.

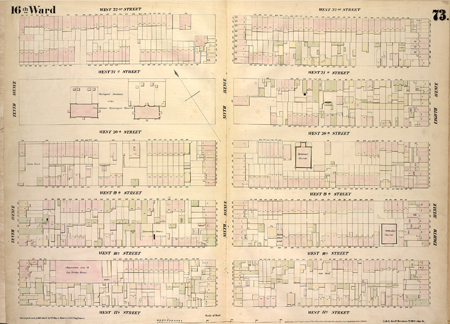

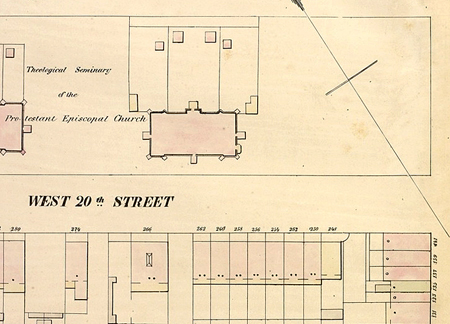

Wood-frame buildings are colored yellow, brick buildings pink and commercial ones green on Plate 73, featuring Chelsea, of the 1854 Perris Map of New York. This insurance atlas also used a system of dots and symbols to convey a structure’s vulnerability and allow fire insurance companies to set rates without visiting buildings. 404 West 20th Street is seen just below the north arrow that’s to the right of the original twin buildings of the largely-open General Theological Seminary block.

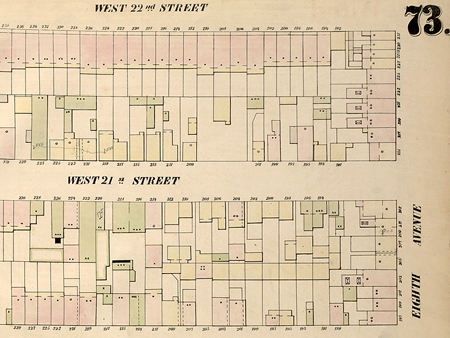

Plate 73 shows scores of yellow-coded frame houses in Chelsea with narrow side yards providing street access to back buildings. Many are visible in this detail of West 21st and 22nd Streets west of Eighth Avenue. These were often modest homes of self-employed tradesmen, which would in time give way to brick rowhouses filling the width of their lots. Sometimes the back buildings came first and were left accessible to the street by passages running next to or through later houses built at the street line. A few of the lots visible above still have only “back” buildings. The map is a snapshot of Chelsea in a moment of transition from village to city neighborhood. The prevalence of this arrangement was specific to Chelsea, as noted in Thomas Janvier’s 1894 city history, In Old New York, which describes “conspicuous features of what once was Chelsea Village”:

. . . even a few of the more modest remnants of that earlier period, the little wooden houses wherein dwelt folk of a humbler sort, still may be seen here and there: standing back shyly from the street in deep yards and having somewhat the abashed look of aged rustics confronted suddenly with city ways. But many more of these timber-toed veterans–true Chelsea pensioners–lie hidden away in the centres of the blocks, and may be found only by burrowing through alleyways beneath the outer line of prim brick houses of a modern time. Notably, on both sides of Twentieth Street, between the Seventh and Eighth avenues, these inner rows of houses may be found; and west of Eighth Avenue on the northern side of the way. But one may rest assured that wherever, in any of the blocks hereabouts, an alleyway opens there will be found an old wooden house or a whole row of old wooden houses.”

404 West 20th Street’s narrow alley is the sole survivor in the Chelsea Historic District, one of only four left in all of Chelsea, and the only one adjoining a wood frame house.

Just two side alleys, each three feet wide, remain on the West 20th Street block Janvier highlighted. #207 (left) has been altered from its traditional rowhouse appearance. A sign on its alley gate reads “207R” for a rear building called a “walk-up apartment” in city records. A handful of Chelsea back buildings live on as residences. Diagonally across the street, #224 (right) recalls the look of 404 West 20th Street minus its distinctive clapboard side wall.

On the same block, an example of Janvier’s “whole row” of back buildings survives behind the Chelsea International Hostel, which occupies historic rowhouses #245 through #259. Their back yards form a long rear court opening to the street through a covered passage under #251. The low row of back buildings has been adapted as hostel units.

248 West 22nd Street rounds out Chelsea’s four surviving side alleys. The rowhouse’s original entrance has been converted to a first floor window and its 3′-7″ side yard to an open-air building entry and stair.

Janvier’s description of antique back buildings as “timber-toed veterans–true Chelsea pensioners” is a sly reference to the wooden legs of military casualties and the man who gave the neighborhood its name, retired British Captain Thomas Clarke. A veteran of the French and Indian War, Clarke bought farmland in 1750 for an estate he wryly named after London’s Royal Hospital Chelsea, which still operates as a retirement and nursing home for British soldiers known as Chelsea Pensioners. It was like calling his last home “the VA hospital.” Clarke’s estate house was located on what became the block south of today’s London Terrace apartment complex. After it burned, his widow replaced it with the one pictured above in Janvier’s book, which would become the home of his grandson, the ancient language professor, slave owner, real estate developer and ” ‘Twas the night before Christmas” poet, Clement Clarke Moore. When northward encroachment of the Manhattan street grid diced Moore’s inherited property into city blocks, he subdivided them into building lots for sale.

Moore donated a full block to the Episcopal Church for use as a seminary. Its campus would double as a town square, giving the community a focus and raising real estate values around it in the manner of contemporary neighborhood greens like Washington Square and Gramercy Park. The Seminary block’s longtime name, “Chelsea Square,” reflects this aim. The large building near the center of the map detail above is the Seminary’s long-demolished 1827 East Building, one of America’s first Gothic Revival buildings. Its twin, the 1836 West Building to its left, still stands, converted to luxury condos in Chelsea’s post-High Line hyper-gentrification. The East and West Buildings fronted on West 20th Street, turning their impressive public faces south to exploit the play of sun and shadow. 404 West 20th Street — the farthest-right house fronting on West 20th Street, colored yellow for its frame construction — was built in 1829-30. Its front garden, side alley and a back building are visible. The map shows the front garden space Moore planned in front of the 20th Street lots to complement the leafy campus across the street. This zone ends in a quarter-circle just right of 404. Moore sold the lots west of 404 to the developer Don Alonzo Cushman, who in 1840 completed what is now considered one of the city’s two best surviving rows of Greek Revival houses, matching the other one on Washington Square and validating Moore’s town-square planning strategy. Cushman’s daughter would later build the Donac apartment building, named for him, on the other side of 404 across its alleyway.

404’s meeting of clapboard and brick shows the direct involvement of Clement Clarke Moore. According to the Landmarks Commission’s 1970 Chelsea Historic District Designation Report:

No. 404, the oldest house in the Chelsea Historic District, was built in 1829-30 for Hugh Walker on land leased from Clement Clarke Moore for forty dollars per year. The lease stated that if, during the first seven years, a good and substantial house was erected, being two stories or more, constructed of brick or stone, or having a brick or stone front, the lessor would pay the full value of the house at the end of the lease. . . . The original clapboard of one sidewall is still visible on the east side of the house.

Moore might have settled for less than an all-brick or stone building in resignation to the lot’s still-open surroundings at the northern city outskirts, land appealing to “folk of a humbler sort,” to get the ball rolling on Chelsea’s development. In stipulating a brick or stone face, this starter house would at least contribute to the dignity and property value he hoped to see at the centerpiece block of his new community. It’s unclear whether his tenant Hugh Walker lived in or used a back building before building the brick-faced house for which Moore reimbursed him, on the model Janvier describes. 404’s brick face may indeed have helped convince Cushman to develop his impressive row next door a few years later. The more humble character displayed behind its brick face makes it the indispensable first page of Chelsea’s domestic history.

The Donac was completed in 1898 to the design of the mansion architect C.P.H. Gilbert. Its form respects the quarter-circle setback Clement Clarke Moore conceived to ease into the adjoining front garden setback. The lowered bay within the Donac’s curve creates the impression that the building is stepping down to the height of its humble neighbor in the same graceful gesture. This masterstroke of suggestion is greatly helped by the alley’s cushion of breathing space between them. Kapoor’s proposed alley infill would bring 404 into formal collision with the Donac.

Moore later took on a property manager, James N. Wells, the carpenter who built St. Luke’s Church in Greenwich Village. Wells moved into the brick house at Ninth Avenue and 21st Street (above) when it was newly-built in 1833. According to a New York Times article by Christopher Gray, Wells

. . . developed the rather sophisticated restrictions that Moore imposed on his lots when private house construction began in earnest in the mid-1830’s. These covenants not only included prohibitions against stables and rear buildings, but also required tree planting. Clearly Moore and Wells were taking pains to create a first-class residential district.

Chelsea’s early frame houses, alleys and back buildings would indeed fade away as the village became Moore’s intended city neighborhood of genteel brick rowhouses, before they were subdivided into apartments for waterfront workers, before they declined in the era of urban flight, before they were rediscovered largely by gay pioneers, before the influx of a few hundred galleries, and before the High Line made it the real-estate jackpot now threatening the layered history and resonance that make it uniquely and richly Chelsea.

Update: In a July 26, 2016, public meeting, the Landmarks Preservation Commission approved a revised proposal which will still replace 404 West 20th Street with a much larger house, fill in its side yard and preserve only its street façade. Commissioner Michael Devonshire alone spoke and voted against the proposal, for “obliterating” the historic house.

More posts on this block of Chelsea:

Buying Michael Bolla’s Chelsea Mansion for Dummies

If the Landmarks Preservation Commission cannot see fit to reject this proposal to raze the oldest house in Chelsea, it should disband and cease its charade of preserving landmarks. By its public remarks, the Commission is demonstrating its ignorance and hostility to preservation as well as to all who care about preserving the historical fabric of our city. Better to recognize the Commission’s irrelevance and disband than pretend that its actions actually result in the preservation of landmarks. Its purview should be limited to erecting plaques describing historic buildings that have been razed or altered beyond recognition.