NYCHA’s Chelsea Plan Collides with Its Residents

Residents of Chelsea's Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea Houses (FEC) protested NYCHA's planned demolition of their buildings with a march and rally on November 8th. The lack of tenant buy-in for the plan is increasingly an issue. The high-profile architecture firm PAU (Practice for Architecture and Urbanism) recently withdrew from the project to demolish and replace the buildings alongside new housing, citing concerns about resident support. In an October 30th lecture at the Spitzer School of Architecture, PAU Principal Ruchika Modi presented a slide of her firm’s mission statement: "PAU is an architecture and urban design studio dedicated to building ecological, equitable, and joyous communities." Challenged by an audience member on the firm’s seemingly contradictory involvement in the NYCHA plan, Modi announced that PAU had bowed out of it because a large number of the residents were opposed to the project.Continue reading→

NYCHA’s Chelsea Gold Mine

A proposed rezoning of Chelsea’s public-housing sites—Fulton Houses and Elliott-Chelsea Houses—could transform much of the neighborhood to midtown-like density. It would introduce towers of up to 39 stories a stone’s throw from early-19th-century Greek Revival rowhouses. This New York City Housing Authority rendering shows new buildings it would construct under the rezoning in gold, viewed...Continue reading→

The Future Still Needs the Gimbels Skybridge

For nearly a century, the Gimbels skybridge has served as a kind of gatehouse announcing Pennsylvania Station on the next block west. Few would guess that its interior was once continuous with the station’s. The bridge will disappear if plans for the Empire Station Complex proceed. This would be a terrible loss. It is by far the most prominent aerial bridge from an era when the rest of the world looked to New York as the skyscraping, multi-level City of the Future—the crowning example of a phenomenon that influenced modern architecture and still captivates and inspires.Continue reading→

New plans still say “teardown” for Chelsea’s oldest house

In an April 19 public hearing, the Landmarks Preservation Commission asked 404 West 20th Street’s new owner Ajoy Kapoor to return with a more appropriate proposal for altering it. Just released, the revised proposal will go before a public meeting of the Commission on Tuesday. The new design takes a little off the top and still...Continue reading→

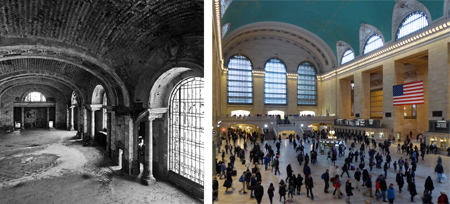

Detroit’s Grand Central: Michigan Central Station

In its much-photographed desolation, Detroit’s Michigan Central Station could be called America’s Ruin, while New York’s restored Grand Central Terminal more than ever lives up to its title as America’s Piazza San Marco. Grand Central was one of New York’s first buildings to be targeted for landmark designation, sparing it from demolition to become one...Continue reading→

Detroit: City of the Future

Henry Ford poses in the first car he made. In his 1922 autobiography, he wrote: “Industry will decentralize. There is no city that would be rebuilt as it is, were it destroyed – which fact is in itself a confession of our real estimate of cities. . . . The modern city has been prodigal, it is...