For nearly a century, the Gimbels skybridge has served as a kind of gatehouse announcing Pennsylvania Station on the next block west. Few would guess that its interior was once continuous with the station’s. The bridge will disappear if plans for the Empire Station Complex proceed. This would be a terrible loss. It is by far the most prominent aerial bridge from an era when the rest of the world looked to New York as the skyscraping, multi-level City of the Future—the crowning example of a phenomenon that influenced modern architecture and still captivates and inspires.

According to a 2014 New York Times piece by Christopher Gray, the bridge was built in 1926 when the Gimbels department store acquired the Cuyler Building across West 32nd Street and hired Shreve & Lamb—soon to be Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, and architects of the nearby Empire State Building—to connect offices in the building to the main store. Gray wrote, “The architects’ design was a no-holds-barred exemplar of the pedestrian bridge, a triplex skywalk with broad windows and magnificent copper cladding.”

Gray observed that, “Although there is classical ornament, such as pilasters and coffers, the flat, machinelike character of the material suggests Art Deco, then barely emergent in the United States.” He noted that in 1982 The New Yorker called the bridge “the Chartres of aerial tunnelry.”

A 1924 skybridge across 33rd Street, also by Shreve & Lamb, linked the other side of Gimbels to the former Saks store. (It is shown being demolished in 1966.) When Saks moved to its Fifth Avenue location in 1922, Gimbels took over the old building, operating it as Saks-34th Street. The tamely classical Gimbels-Saks bridge shows how far its architects’ style stepped into the future by the time of the Gimbels-annex bridge two years later.

The two Gimbels bridges were part of a layered transportation arrangement for which New York was world famous. The streets beneath these bridges passed in turn over the subway, accessible through the Gimbels store. A pedestrian tunnel also connected Gimbels to Pennsylvania Station, passing beneath the Hotel Pennsylvania and Seventh Avenue. One could have entered this enclosed system through Gimbels, its annex, or Saks-34th Street and next stepped outdoors in Chicago, having accessed Penn Station through the connecting bridge-tunnel-building network.

The Hotel Pennsylvania and the Governor Clinton (now Stewart) Hotel were also part of this network, linked to the station by tunnels under Seventh Avenue. An out-of-towner could arrive by train at Penn station, get a haircut in its barber shop, buy underwear in Gimbels’ bargain basement and a suit at Saks, wear them to dinner in a station or hotel restaurant, listen to a big band in the Hotel Pennsylvania’s Café Rouge, sleep in one of the hotels’ thousands of beds, breakfast in the station’s cafeteria, and return home—without ever stepping outdoors. The linked buildings provided enough services to amount to a city within a city. Like their contemporary mixed-use complex at Grand Central Terminal, they anticipated the megastructure movement of the 1960s and 70s which melded buildings to transportation and aspired to place the full range of urban functions under one roof. In his 1976 book, Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past, Reyner Banham wrote that “patriotic Gothamites eager to claim the concept as a New York invention” could point to Penn Station, Grand Central, and Rockefeller Center. The movement had peaked by the time of his writing but it moved architecture’s needle. It’s ideas still guide leading architectural theorists like Rem Koolhaas and Steven Holl.

Shreve, Lamb & Harmon’s Art Deco Empire State Building is seen beyond their proto-Deco Gimbels skybridge which Christopher Gray called “one of the city’s great works of metal.” Both were designed in the late 1920s, a mythic period of concentrated activity when the exuberance of New York architecture reached a crescendo and many of the city’s best-loved and most defining works were produced. Both structures were the apotheosis of their type, the aerial bridge and skyscraper, which in combination dominated early-twentieth-century visions of cities to come. When Kuala Lumpur’s 1998 Petronas Towers followed in the Empire State Building’s footsteps as the world’s tallest buildings, their linking skybridge carried the DNA of this imagery.

The Empire State Building’s top, another of the city’s great works of metal, was touted as a mooring mast for zeppelins. Impractical for this use, its real purpose was to contribute to the building’s record-setting height. The mooring-mast claim was telling, though. The skies of urban fantasies inspired by New York were alive with airships. It’s as if the Empire State Building’s designers felt obliged to deliver. Like skybridges and skyscrapers, lighter-than-air vehicles resisted gravity. These ingredients mixed to create popular urban visions that promised liberation from an earthbound existence.

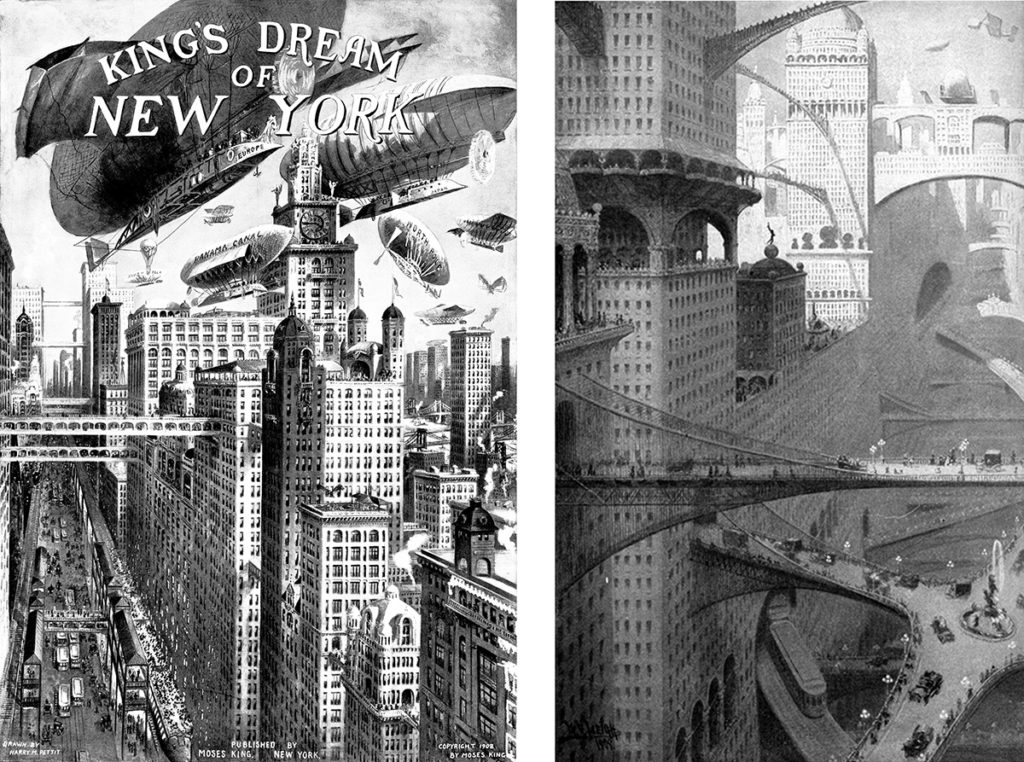

Images like Harry M. Pettit’s rendering for Moses King’s guidebook, Views of New York, and William Robinson Leigh’s painting, “Visionary City,” both from 1908, exaggerated New York’s towers and aerial pathways to project the future. Practicality aside, these cityscapes looked thrilling to inhabit. Aerial bridges allow people to magically step through building façades and cross streets in the air. Space takes on dizzying visual depth and unprecedented three-dimensional navigability. All of this plays to our fundamental condition as mobile bodies in space possessed of free will. The immersive motion in these images coincided with the advent of popular movies which also appealed to the modern appetite for speed, daring, and excitement.

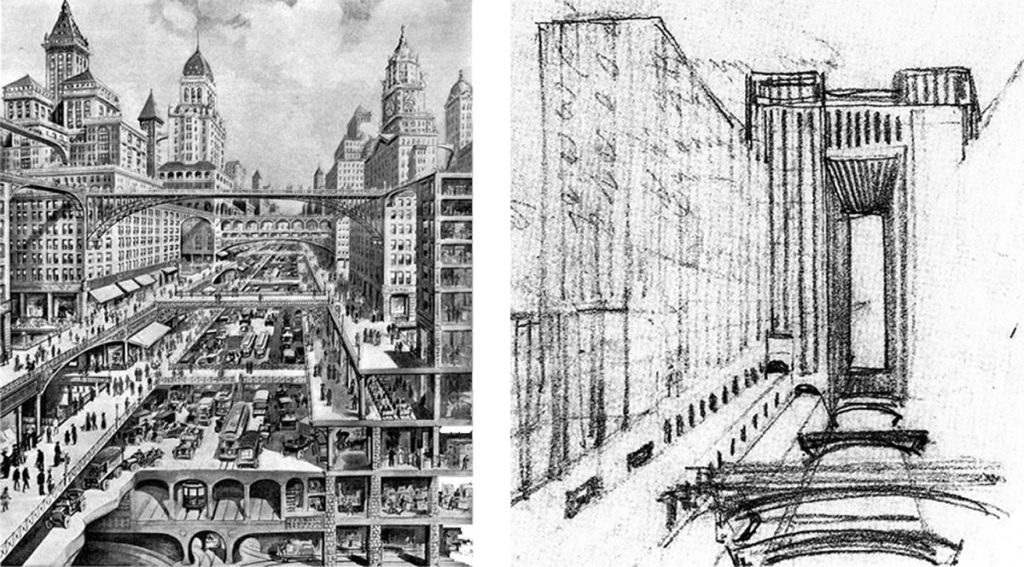

The illustration at left was featured on the cover of Scientific American in 1913 and reproduced the same year as “The Circulation of the Future and the Cloudscrapers of New York” in the Milanese magazine L’Illustrazione Italiana. Such images inspired the influential Milan-based Italian Futurist movement, as seen in Antonio Sant’Elia’s study for his project La Città Nuova (The New City) at right.

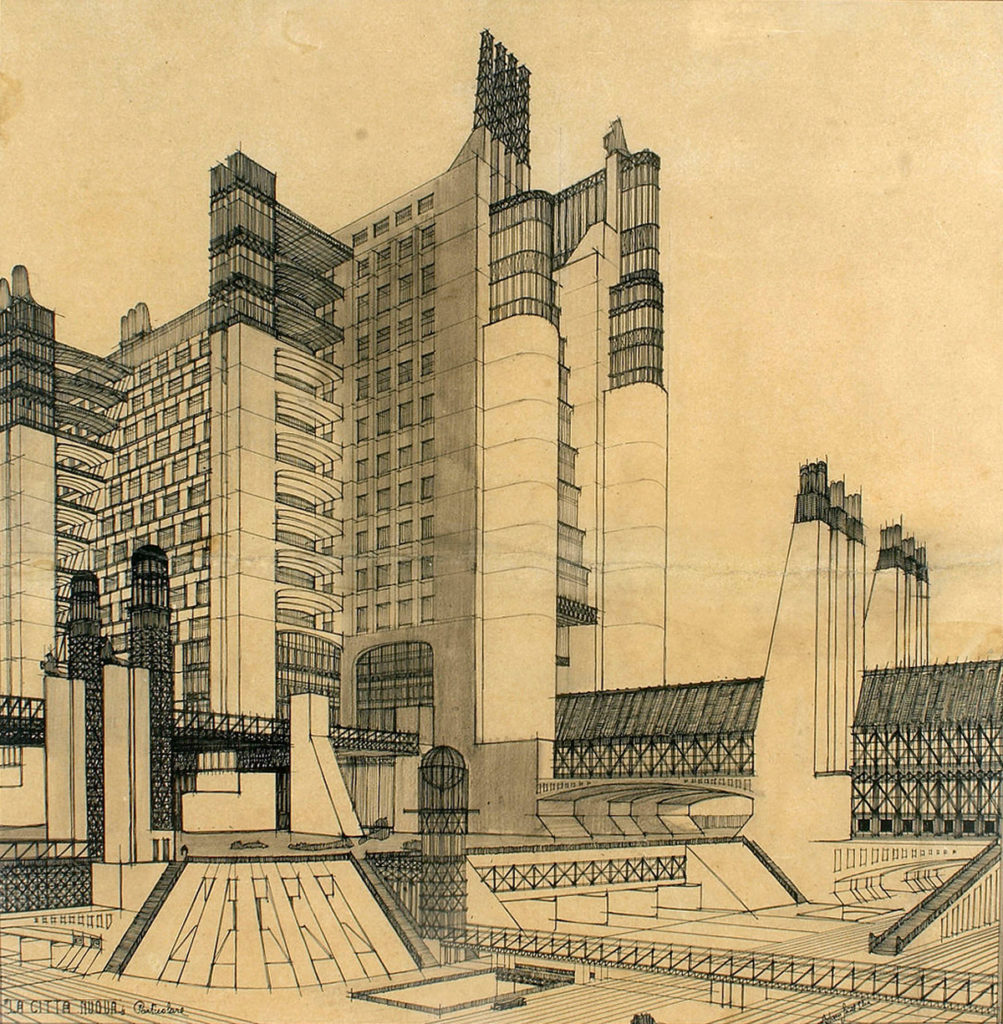

This 1914 rendering is Sant’Elia’s most fully developed rendering of La Città Nuova. (He was killed two years later in World War One at just 28.) Bridges, overpasses, and transportation systems aren’t tacked onto the static buildings of a traditional city, but used as the building blocks of a new kind of dynamic, city-scale structure that jettisons architectural history.

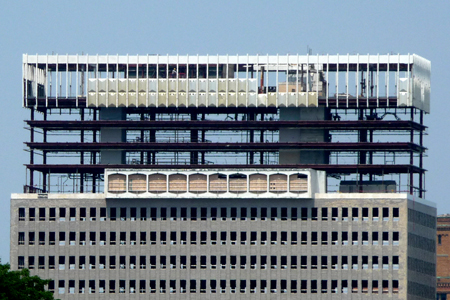

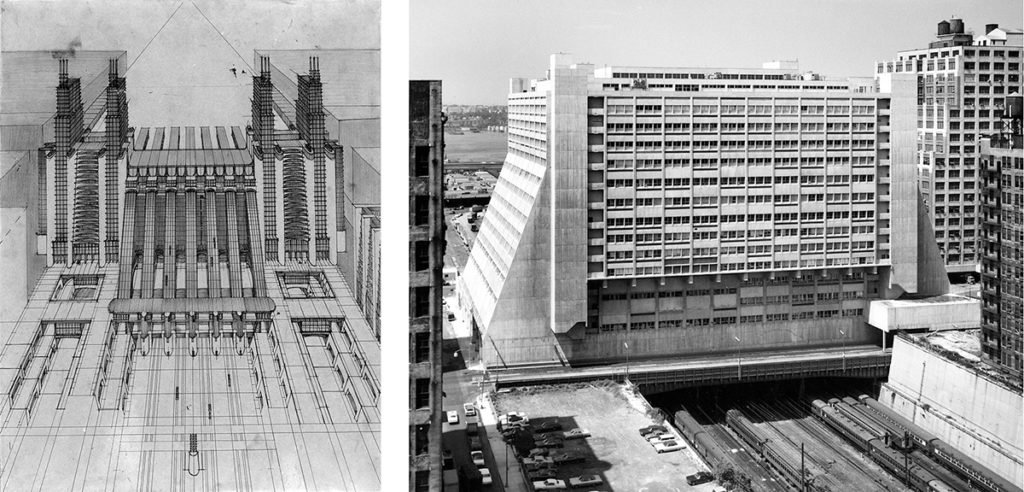

In the 1914 image at left, Sant’Elia imagined a station for airplanes and trains with funiculars. Manhattan’s Westyard Distribution Center at right was designed by Davis Brody and opened in 1969—one of countless buildings around the world influenced by Sant’Elia’s unbuilt body of work. The historic photo shows Westyard straddling the West Side Rail Yards. It has been renovated as Five Manhattan West. The block of the railyard beyond it has been decked over and developed as Hudson Yards. The block in the foreground has been decked over and developed as part of Midtown West, with a central pedestrian mall running from Five Manhattan West to Ninth Avenue directly opposite the west entrance of the new Moynihan Train Hall. The mall’s axis resumes on the other side of Moynihan Train Hall and Penn Station as 32nd Street, passing directly under the Gimbels skybridge like a through-line of architectural history.

Five Manhattan West, formerly Westyard, is seen with its newly enhanced dynamic diagonals at upper right in this rendering of the High Line’s planned Moynihan Connector. The pedestrian bridge will link a tree-covered extension of the High Line’s spur to the new Manhattan West mall (a right turn just past the pink-flowering trees) which approaches the Train Hall. Another connector will link the north leg of the High Line to the west terrace of the Javits Center and a long-planned but never-built pedestrian bridge over the West Side Highway to Hudson River Park. Together with the High Line itself, this pedestrian network, raised above street traffic, may be one of the closest things ever built to those layered-city magazine fantasies that inspired Sant’Elia and the Futurists.

Fritz Lang said his classic 1927 film Metropolis was inspired by a 1924 visit to New York. It was also clearly influenced by futuristic visions of New York and Sant’Elia’s projects, as have been science fiction movies from Blade Runner to Brazil to The Fifth Element, the latter featuring a future New York dense with skybridges and flying taxis. The richly activated three-dimensionality of early visions on paper is inherently cinematic, as witnessed by countless cinematic shoot-outs on the monkey-bar catwalks and ladders of abandoned warehouses. Forward-looking architecture naturally shares territory in the future with science fiction; Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1924 Ennis House was still out-there enough to portray 2019 Los Angeles in Blade Runner.

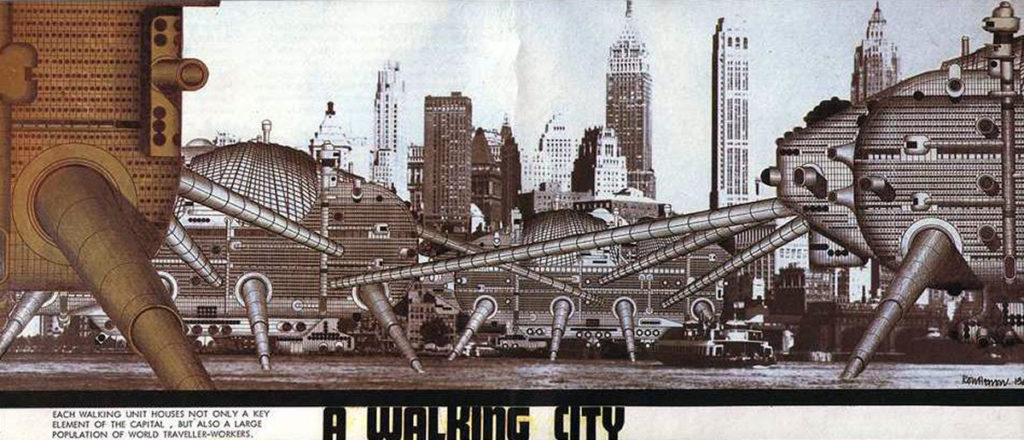

This rendering of the 1963 Walking City project by the avant-garde architectural group Archigram is captioned: “Each walking unit houses not only a key element of the capital, but also a large population of world-traveler-workers.” With its leg-like bridges, the Walking City is in the futuristic skybridge-city tradition. It is also in the city-within-a-city tradition of interconnected buildings forming self-contained complexes like the ones centered on Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal. The scheme does the motion-infused city one better—the city itself moves. Reyner Banham included this image in Megastructure, writing of its units: “Their location here in the East River, with the towers of Manhattan in the background, suggests a deliberate challenge to older visions of the future.”

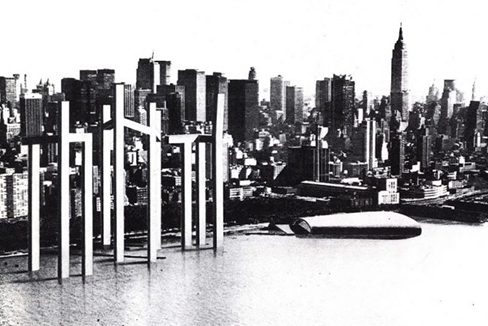

Freed from the land and knee-deep in the Hudson against a backdrop of midtown skyscrapers, Architect Steven Holl’s 1990 Parallax Towers project mirrors Archigram’s Walking City on the opposite side of Manhattan. Its “hybrid buildings” with diverse functions would be connected both underwater and by skybridges.

Holl’s 2009 Linked Hybrid project in Beijing shows that his Parallax Towers scheme was far from a pipe dream. Its eight towers linked by eight bridges house 2,500 residents and recall Matisse’s ring of dancers clasping hands—an apt metaphor for Holl’s intent to un-silo residents, generate random relationships, and “express a collective aspiration.” (They also recall Gimbels when it had a bridge on each side like outstretched arms.) The skybridges contain a swimming pool, fitness room, café, and gallery. Holl’s description places the complex in the best cinematic, layered-city, proto-megastructure New York tradition:

As a “city within a city” the new place has a filmic urban experience of space; around, over and through multifaceted spatial layers. A three-dimensional public urban space, the project has programs that vary from commercial, residential, and educational to recreational.

In this dazzling project, New York’s early skybridges reverberate across a century and around the planet. Linked Hybrid shows that their progeny can be part of a sunnier future that the dystopian ones science fiction movies depend on for dramatic tension and noir atmosphere.

SHoP Architects’ American Copper Buildings were completed in 2018. The project’s towers are connected by a bridge containing a lap pool and lounge, touted as the highest skybridge in New York City and the first to be built in decades. It is proof of the continuing power of the Gimbels bridge, just the other side of the Empire State Building, to inspire.

What does the future hold for the Gimbels skybridge, the “Chartres” of those early spans that gave so much to the future? It cries out for the landmark designation that would protect it, but this would require also designating of the old Gimbels and Cuyler buildings that hold it up. It’s impossible to imagine this being done by our current Landmarks Preservation Commission, which wouldn’t even designate McKim, Mead & White’s adjacent Hotel Pennsylvania a landmark. The Gimbels store clearly merits consideration for landmark status. It was designed by Daniel Burnham, one of the nation’s most influential architects and urban planners.

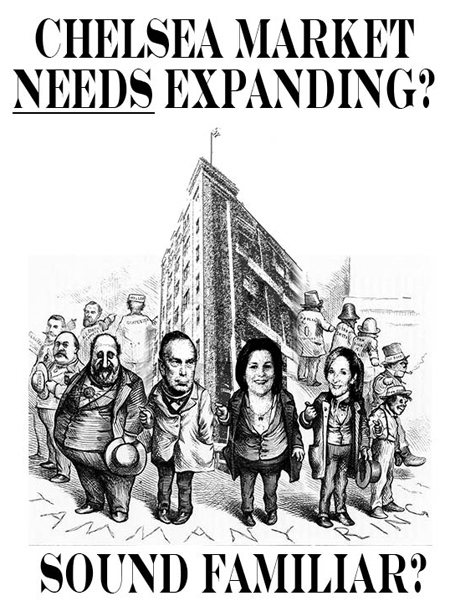

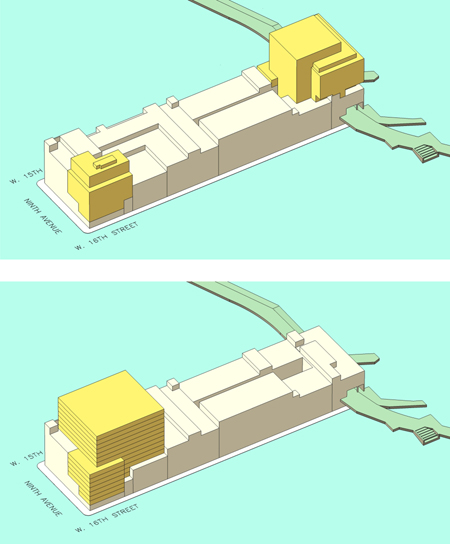

Christopher Gray’s article stated that the buildings connected by the skybridge have been separately owned since 1994 and that plans were filed in 1995 to remove it. He speculated that the daunting cost of demolition may have stayed the bridge’s execution: “Perhaps money alone is preserving our 20th-century Chartres.” This might be enough to keep it aloft indefinitely were the Empire Station Complex abandoned. If the plan is approved, its zoning changes would greatly increase the built square footage allowed on the Gimbels site. Like most of the property that would be transformed by the Empire Station Complex, the site is owned by Vornado Realty Trust. The more extra area Vornado is allowed to build there, the less reason for it to reuse Gimbels and the more to demolish it and its skybridge, and build all new. In a better world, Vornado would recognize the cultural and potential market value of its property, and incorporate it as the base of any taller building allowed by zoning. Or the Empire Station Complex plan might be modified to make zoning increases contingent on this. That would take the intervention of more enlightened leadership; the project’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement states that there are no historic resources on the Gimbels site.

Even if no longer used as a connector, the Gimbels bridge is wide enough for its three levels to follow modern-skybridge examples and contain programmatic space. It could house tenant-attracting board rooms, lounges, or other amenities with dramatic views, accessed from one side. A little imagination and New York know-how could allow other landmark-worthy structures in the Empire Station Complex’s path to be saved without defeating the plan’s purpose. Foundations could certainly be reconfigured under Saint John the Baptist Church and the Penn Station Powerhouse to allow new tracks and platforms below. Blending authentic New York texture with new development would add great appeal. Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story, from its opening to closing credits, is a paean to the established texture of New York. Not surprisingly, the film includes a likeness of the Gimbel’s bridge.

Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie is a mixed-use complex in the megastructure tradition, housing concert halls, restaurants, bars, conference rooms, a hotel, a spa, apartments, and parking. Designed by Herzog & de Meuron and completed in 2016, the project reuses a nondescript 1960s brick warehouse as its base. The warehouse reads as an underlying archaeological stratum, expressing how Hamburg’s cultural present is built on its geography and history as a working port.

The Gimbels store could similarly serve as a value-adding base for an even larger building. Its famed designer and architectural merit aside, the building tells of the neighborhood’s intertwined garment-center and retail-district histories. Gimbels was the major competitor of nearby Macy’s, and was completed in the same year as the original Penn Station, near which it was strategically built. Such buildings tell how a neighborhood came to be. They give it historic resonance and a unique identity that can’t be made from scratch—the sort of authentic character that makes people want to live in places like New York. Recycling this embodied history would complement the environmental sustainability of adaptive reuse, for which Gimbels cries out. The nearly million-square-foot structure has enormous embedded energy, high structural capacity, tall ceilings, and abundant windows. It could be adaptively reused for any number of purposes.

Imaginative reuse of old buildings has earned growing recognition not just on environmental grounds, but critically. Last year’s Pritzker Prize—architecture’s highest honor—was awarded to Lacatan & Vassal, the French firm that prides itself on never having demolished a building to construct a new one. This is the direction of the world’s enlightened architecture today—the reverse of what the Empire Station Complex proposes. The plan’s reversion to Robert Moses-era clearcutting of whole city blocks is a special embarrassment for a city that once led the world into the future.

The Empire Station Complex would follow the formula of the unloved Hudson Yards development, but its destruction of historic architecture will make it even more regrettable. New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman put his finger on Hudson Yards’ defining failure, writing that it gives physical form to “a pernicious theory of civic welfare that presumes private development is New York’s primary goal, the truest measure of urban vitality and health, with money the city’s only real currency.” Historic architecture that continues to engage the imagination and inspire is another, very real currency. Miami wouldn’t be the international brand and destination it is if South Beach’s Art Deco hotels had been replaced by larger ones rather than preserved. Who visits or moves to New York for Hudson Yards? It’s Teflon to the imagination, just as the Empire Station Complex promises to be—the very opposite of the mythic New York embodied in the Gimbels skybridge.

photo credits:

American Copper Buildings NY1 (cropped).jpg by Acroterion CC BY-SA 4.0 Int’l

Elbpjilharmonie, Hamburg.jpg by Hachercatxxy CC BY-SA 4.0 Int’l.