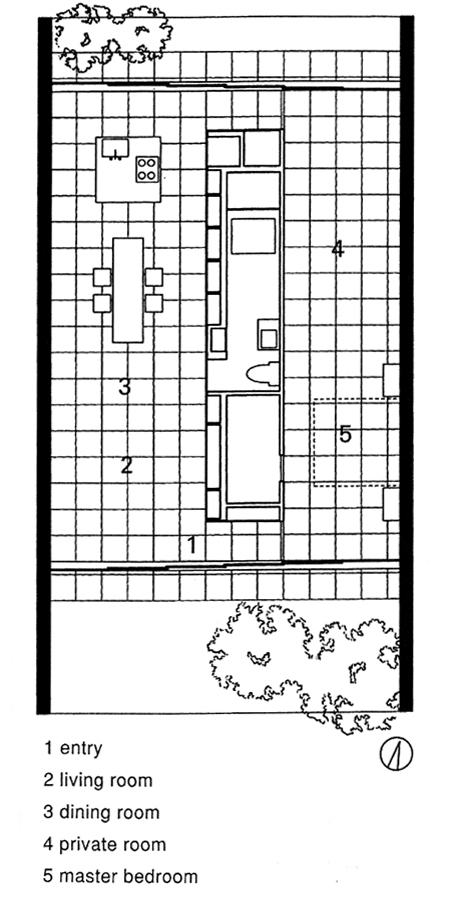

Shinichi Ogawa’s 2002 Abstract House could illustrate any of the ten House Rules. It demonstrates not just their compatibility, but their potential to enhance each other. In exploiting the strategies on which the rules are based, this modest house efficiently summons spatial luxury and an undistracted connection to nature from an ordinary site.

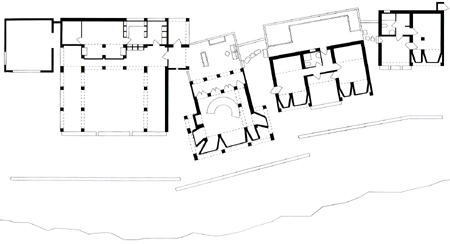

Ogawa’s floor plan successfully transplants lessons from Mies van der Rohe’s bucolic Farnsworth House into Japan’s Onomichi City. Its long side walls extend into the outdoors to embrace a small court at each end. The courtyard walls provide privacy from nearby houses and block street level distraction. The design’s minimalism gives the tiny courts a disproportionate impact, letting nature and atmospheric conditions set the tone of the house in a more dynamic and affecting way than any decorating scheme; not as pervasively as in a glass-box house but with much bigger bang for the pane. (Pivoting panels at either end of the service core can be closed to seal off the more private zone, at right above, or stand open to replicate the Farnsworth House’s spatial loop.)

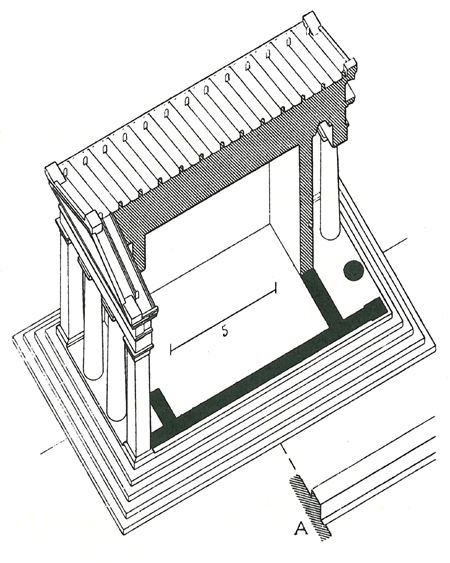

The idea for House Rules grew out of a conversation with a couple who asked for a critique of a plan they had found and liked in a book of house plans. From the perspective of an architect, the design was disappointing but it was hard to say why. Singling out shortcomings didn’t sum up what was wrong with it and only seemed nitpicking. The problem wasn’t so much with what the plan was, but all that it wasn’t. A copy of James Ackerman’s book on Palladio was within reach, and next we were looking at a plan of the Villa Foscari: “See how both the house and its individual rooms are all perfect shapes, as if they were designed at once, and nothing feels like leftover space?” What would be House Rule 3 was born.

The rules presuppose small houses and reflect personal preferences, but a case can be made for their validity on both counts.

Small houses make sense for sustainability and in response to America’s soaring percentage of one- and two-person households, which are now the national norm. Houses designed for such small households are freed from substantial privacy and partitioning needs, and can pursue exciting spatial opportunities in their place, much as sports cars are freed from back seats and sensible hardtops.

Small houses can also bring custom design into reach. Lending practices require more money to be spent up front on land acquisition and construction for self-built homes as opposed to purchase of ready-made development houses. Economic necessity funnels the vast majority of new home buyers into speculative tract houses that aren’t based on what most of us want, but on marketing assumptions aimed at maximizing profits across the boards. Developers seem to take Frank Lloyd Wright’s view of the American house – a box full of boxes with holes punched in it for windows – as a description of what Americans really want and a recipe for sales success rather than a complaint. If Americans were more willing to live in compact, affordable houses, many more would be in a position to finance custom designs. They’d be living in smaller but better-fitting homes, and the typical American house would look very little as it now does. The House Rules aim to encourage this alternative by optimizing the quality of space and experience in such houses, adding value through inexpensive or cost-free design decisions.

Beyond economic considerations, whatever validity the House Rules may claim lies in the merit of the great houses from which they’re derived. It became clear in assembling them that individual rules could not only be illustrated by the majority of iconic modern houses, but that most of the houses used as examples embodied most of the rules.

The House Rules are an introduction to the possibilities that lie beyond developer housing. They aim to get more Americans into houses designed specifically for them by an architect. The rules aren’t meant as a substitute for an architect, but a prelude to a conversation with one.