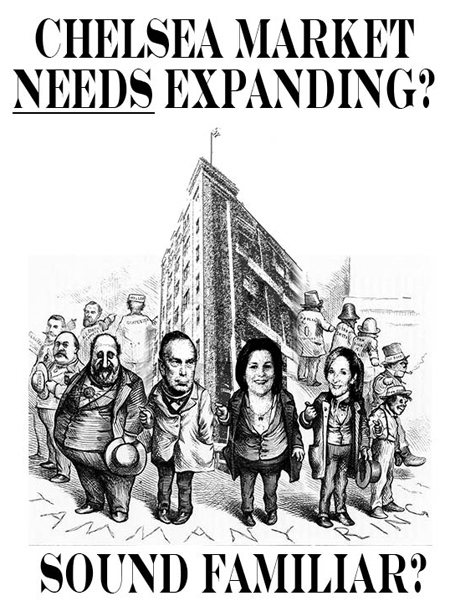

From right to left, Amanda Burden, Christine Quinn, Mayor Bloomberg and Boss Tweed reprise Thomas Nast’s ring of passed blame around Chelsea Market in a flyer that’s started appearing on Chelsea streets.

On October 19th, I and others met with City Council Speaker Christine Quinn to discuss Jamestown Properties’ proposed rezoning of Chelsea Market, aimed at adding over a quarter-million square feet of office space to the historic complex. I twice asked Speaker Quinn just how she saw the proposal making sense on zoning basics of use, bulk or environmental impact. She would only say that she hadn’t completed her review, but then still had no answer when we met six days later, just before the City Council’s land-use committee voted to support the proposal, surely with Quinn’s endorsement. Only Speaker Quinn could have stopped the project, but she advanced it in the face of overwhelming community resistance and without being able to say how it was good zoning.

If Speaker Quinn is already beholden to real estate interests in her expected run for mayor next year, she promises to bring to that office a fourth term of the Bloomberg administration’s worst feature; a pro-development, anti-oversight bias. In this New York, real estate runs politics and deals trump zoning. In a New York Times article on the Council’s Chelsea Market vote, David Chen wrote that in remaining “conspicuously quiet about the issue” and failing even to attend a public hearing on it, Quinn “left little doubt . . . that she had been the driving force behind the deal.” It’s pretty official when the Times calls it a deal.

Speaker Quinn had no answers about the Chelsea Market plan’s zoning merits because there are none. So how was the proposal approved? By a system that promises more of the same. Speaker Quinn’s and the City Council’s votes are part of ULURP, the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure that’s supposed to let the public and city officials participate in reviewing and approving development. In theory, the review process begins when a project is certified by the Department of City Planning. In practice, certification by the Department guarantees a project will go forward, rendering ULURP pointless except to provide a retroactive veneer of democratic process. Only one project in recent memory has been certified and not built, and that was under atypical circumstances. City officials and community board members who weigh in under ULURP can’t vote an unqualified “no” on a project without being ostracized for refusing to play ball and losing the chance to earn give-backs. On the Chelsea Market proposal, for example, Community Board 4 voted “no, unless” Jamestown funded off-site affordable housing. Several of Chelsea Market’s ULURP participants told me that voting the flat “no” in their heart would be futile and waste a chance to salvage some community benefit. After ULURP, City Planning can count such forced hands as raised in support. The system is perfectly rigged to cloud responsibility and foster deals. Projects may be scaled back during ULURP, but developers can pad their projects in anticipation. The Chelsea Market proposal has been scaled back slightly, creating an illusion of a functioning review process that Speaker Quinn and the Department of City Planning can cheaply trumpet.

Officials involved in ULURP seem desperate for any tweak or offset to deflect community criticism and make them appear to have done right by the public, while approving projects regardless of merit like the political animals they are. In meetings I and other community members had with Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer and Speaker Quinn during their respective turns at ULURP deliberation, we were pressed from the start to tell what concessions or give-backs would satisfy us. Both Stringer and Quinn were more interested in making the project palatable to us than hearing why it shouldn’t be built. The Borough President and members of his impressive land-use staff, who are a credit to him, grasped the proposal’s lack of merit and its motivation in greed to cash in on views over the High Line. Despite this worthy analysis, ULURP’s political reality apparently prevented the Borough President’s flat rejection. At least he acknowledged the lunacy of building over the High Line, voting “no, unless” Jamestown’s addition was shifted to the Ninth Avenue end of Chelsea Market and scaled back. If City Planning was really interested in such informed ULURP input, it wouldn’t have ignored the detailed and compelling substance of the Borough President’s recommendations. City Planning left most of the addition over the High Line in its own later recommendations.

Permission to build above the High Line was clearly set in stone from the start, as witnessed by its survival though a review process that sometimes spotlighted its zoning folly. If this was one side of a deal that had to be honored, the other was Jamestown’s payout of about $17 million into a High Line maintenance fund. To those who see Jamestown’s proposal as simply wrong, no give-backs can make it right. Accepting them would be like allowing wrongdoing on Wall Street for a cut of the action. To the extent that Friends of the High Line was in on the ground floor of such a deal, it can be said to have encouraged zoning abuse for financial gain. It shares both spoils and blame with Jamestown. City Planning created some cover for this in September, when it diverted $4.7 million of Jamestown’s payout into affordable housing, answering Community Board 4’s earlier approval condition. (Housing experts say such funding promises often grease zoning changes through without ever producing new affordable units.) To some, this diversion of funds only reinforced the impression of a deal by seeming to explain the earlier surprise appropriation of $5 million to the High Line by the City Council in June’s city budget agreement. In July, Matt Katz of DNAinfo wrote that “The move has some park advocates questioning why the city is set to spend on the High Line such a large part of its $105 million, 2013 appropriations for 142 park projects — when the taxpayer money could go to other city parks that have greater infrastructure needs and fewer wealthy donors.” Factoring in this gift from Speaker Quinn’s City Council, the High Line’s $17 million side of the deal should be preserved.

What else but a deal could explain Robert Hammond’s perverse cheerleading for Jamestown’s tower over the High Line? His park would have earned just as big a payout if Jamestown built its whole project at the far end of Chelsea Market, where it wouldn’t rob the High Line of sunlight, sky views and open space, and would sensibly be closer to subways and Google’s headquarters. Jamestown critically needed Hammond as a spokesman, which he must have agreed to be from the start. He dutifully told whoppers for Jamestown at the City Planning ULURP hearing on July 25th, testifying that “The High Line was designed to interact with neighborhood buildings, even changes in the skyscape that take place around it.” (Never mind that the skyline immediately around Chelsea Market was deliberately sculpted by existing zoning to complement the current height of Chelsea Market at a critical location.) City Planning Chair Amanda Burden beamed at Hammond as he explained, “People love architectural variations around the High Line. We don’t think they’ll detract from the experience of being on the High Line at all.” As for shadows Jamestown’s tower will cast on the High Line, Hammond said people seek shade underneath the High Line as it is. (Never mind that the tower will cast its longest shadows in colder months, putting most of the park’s Tenth Avenue Square grandstand feature in shadow when warming sunlight would increase its use.) Hammond even said High Line visitors won’t see Jamestown’s tower because the grandstand faces away from it, paying Jamestown’s design the highest praise it’s earned to date.

Robert Hammond is a folk hero and the apple of Amanda Burden’s eye for having conceived of the High Line, but its success now has many legitimate fathers. These include talented architects and dedicated advocates like Ed Kirkland, who helped create the park and was the primary author of the Special West Chelsea District zoning which protects High Line open space and reduces the height of new development as it approaches historic surroundings. In a recent New York Times profile, the 87 year-old Mr. Kirkland said of Jamestown’s proposal, “I promise that there is no reason for this to happen except financial reasons that benefit Jamestown. It does not do the city or Chelsea any good. It’s bad for the High Line . . .” There’s no better authority; for fifty years, no one has given as much of himself as Mr. Kirkland to Chelsea’s preservation and planning. “If I wasn’t used to the city, I would be outraged,” he added in a public forum on October 18th.

The High Line was also created with over a hundred million dollars in public funding, making stakeholders of all New Yorkers. Although Robert Hammond doesn’t seem to appreciate the value of others’ High Line contributions, he’s been uniquely entrusted to barter them. He also seems unaware of the backlash that may come of the ugly spectacle he’s created: Jamestown shoving past the public to hog prime space on a High Line it sees as a money-trough. The damage isn’t limited to the High Line. Chelsea’s residential character and historic authenticity will suffer, and the neighborhood made more like Times Square, a place of office towers and tourists, avoided by New Yorkers. Like Chelsea Market’s historic sensitivity, the rest of Chelsea is forgotten under the reigning High Line mania. Hammond’s failed 2009 attempt to have neighboring blocks taxed for High Line operating costs still rankles in Chelsea. In a public meeting on Jamestown’s plan last year, Community Board 4’s Corey Johnson voiced a growing neighborhood mood, repeating, “I resent having the High Line used against us.”

Most New Yorkers I speak to are still unaware of what’s planned for Chelsea Market, but it’s coming soon, in 3D. There will be many a “who let that happen?” Frank Lloyd Wright claimed his buildings were portraits of his clients. Has Jamestown’s architect, David Burns of STUDIOS Architecture, made his Chelsea Market design a group portrait of those behind the project? Maybe he’s a better architect than we think.

ULURP promises more ugly pictures. As Speaker Quinn’s lack of answers attests, the process isn’t about responsible planning, but deals. ULURP reform cries out to be made an issue in the upcoming mayoral campaign. After what she’s condoned at Chelsea Market, it’s not a cause Quinn can claim. After so bitterly letting down her own council district, one wonders just what she can claim to the rest of New York.

While Chelsea Market is a lost cause, it may be a big enough outrage to rally change, like Penn Station’s demolition, which was just as foolishly justified by the promise of jobs.

The entire Special West Chelsea District is already zoned C or M, allowing office construction throughout. The district is one of the most underdeveloped parts of Manhattan. Jamestown could build here, but that wouldn’t enrich property it already owns, Chelsea Market, which lies just outside the existing district boundary at lower right. Only three sites in the Special District are now eligible for the High Line Improvement Bonus. They are shown shaded at the bottom of the district map above. The one on the right has already been developed as the Caledonia apartment building. The one at lower left is the parking lot site shown in the photo below. Jamestown wants Chelsea Market brought into the Special District to exploit the bonus, which is described in text accompanying this map on City Planning’s website:

In recognition of the unique condition of the High Line between West 16th and 19th streets, where it broadens and crosses over 10th Avenue, adjacent development on these blocks could receive additional floor area through . . . restoration, remediation, and implementation of the High Line open space . . . at perhaps its most prominent location.

Jamestown will turn this bonus from a reward for cultivating open space into a reward for seizing it from the park “at perhaps its most prominent location.”

Chelsea Market is at upper left in this view looking south above the High Line where it crosses Tenth Avenue. Below it, the high-rise Caledonia apartment building steps down to complement the market’s existing height and give space to the High Line where it passes through Chelsea Market. This carefully planned, fully executed and successful piece of the park’s design will be undone by a zoning change allowing a new office tower above Chelsea Market and the High Line. This change can only be said to benefit Chelsea Market’s owner, the real estate investment firm Jamestown Properties. A zoning change would have merit where there was demand for a given use, need for new space to build it, and an absence of negative impact on community resources like historic structures or a public park. All of these fundamentals condemn Jamestown’s proposal. The only demand or need are Jamestown’s, as witnessed by the block at lower right above; a few hundred feet from Chelsea Market, it’s zoned to allow office construction, but remains a parking lot. As one of two remaining lots in the Special West Chelsea District eligible for the High Line Improvement Bonus, it’s poised by design to provide the park a payout and open space in return for a floor area bonus. Its open space contribution is already designed as the park’s centerpiece, 19th Street Plaza, which will occupy the lot’s wedge of space between the High Line and Tenth Avenue. As modeled in ArchiTakes earlier, this feature will be adversely affected by Jamestown’s addition. Apparently, Robert Hammond couldn’t wait for the parking lot’s inevitable development and supported application of the High Line Improvement Bonus to Chelsea Market because Jamestown was ready to build there. The bonus’s entire open space purpose will be conveniently reversed, for Jamestown’s enrichment.

More on Chelsea Market:

Is the City Building Google a High Line Skybox? – July 5, 2012

High Noon at Chelsea Market – March 20, 2012

Jamestown’s Shady Plan for Chelsea Market – November 22, 2011

What New Zoning Could Mean for Chelsea Market – May 31, 2011

Saving Chelsea Market – March 22, 2011