This image by Owen Freeman illustrated last month’s New York Times post-Sandy op-ed by James Atlas, “Is This the End?” Freeman says in his blog that it was commissioned by Times Art Director Erich Nagler, who “proposed an underwater, Atlantis-type view of New York City.” Freeman shows working sketches for the Statue image as well as underwater views of Grand Central Terminal and a city intersection with skyscrapers. The Times’ selection of his Statue of Liberty image says something about what rattles us most. It also extends a long tradition of using the statue as a post-apocalyptic milestone, one with roots pre-dating the statue itself.

The Statue of Liberty is seen even farther submerged by global warming, but from above the water line, in Steven Spielberg’s 2001 Science Fiction film, A.I. As a sci-fi film device, this image has a clear heritage . . .

Franklin J. Shaffner’s 1968 film, Planet of the Apes, ends with this visual kicker, revealing that – spoiler alert! – the planet ruled by apes is no less than our own future earth, turned into a vast desert by man himself. Same recipe as now, but with sand substituted for water.

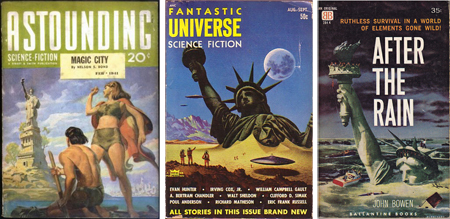

Planet of the Apes may have been the first film to show a ruined Statue of Liberty, but the idea has a longer history in print, as documented by the surely pseudonymous Joachim Boaz in his blog Science Fiction and Other Suspect Ruminations. He displays no fewer than six pulp science fiction covers showing the statue underwater, buried in desert sand, and discovered by spacemen or post-apocalyptic primitives. Selected above are, left to right, a 1941 magazine cover by Hubert Rogers, a 1953 magazine cover by Alex Schomburg and a 1959 novel cover by an illustrator known only as Blanchard. These might be assumed to reflect Cold War insecurity, except for the Astounding Science Fiction cover from pre-Bomb 1941, which shows an overgrown statue approached by raft-borne throwbacks. Clearly, there’s something older at work.

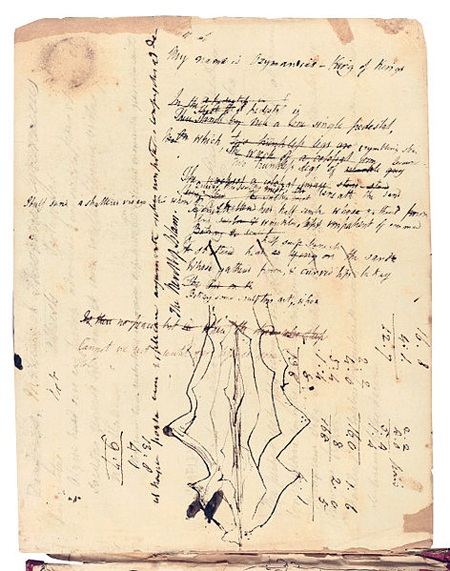

The Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1817 draft of Ozymandias, from Oxford’s Bodleian Library, includes squiggles that might be a premonition of a certain green gown. It reads:

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown

And wrinkled lip and sneer of cold command

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed.

And on the pedestal these words appear:

`My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away”.

The statue’s arrogance might throw one off the scent, but the use of a shattered human form as a cultural momento mori undeniably sets the stage for our 71 year-old ruined-liberty trope. “Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair” kicks the ladder from under whoever’s currently on the top rung. Shelley, influenced by the revolutionary writings of Thomas Paine, is thought to have been targeting the oppressive monarchy of George III.

Shelley’s poem resulted from a sonnet-writing competition with his friend Horace Smith in which both would take as their subject a ruined statue of Ramses II (photo: Mutjaba Chohan). It had recently been acquired by the British Museum and was then bound for London. Smith’s poem was originally also called Ozymandias, as the Egyptian Pharaoh was known in Greek sources. The Guardian published Shelley’s entry on January 11, 1818, and Smith’s on February 1, 1818. Smith’s version is a more direct warning to his world-dominating homeland:

In Egypt’s sandy silence, all alone,

Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throws

The only shadow that the Desert knows.

“I am great Ozymandias,” saith the stone,

“The King of kings: this mighty city shows

The wonders of my hand.” The city’s gone!

Naught but the leg remaining to disclose

The sight of that forgotten Babylon.

We wonder, and some hunter may express

Wonder like ours, when through the wilderness

Where London stood, holding the wolf in chase,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What wonderful, but unrecorded, race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.

Smith is no Shelley, but in depicting a future regression of the human race he makes an astonishing leap into modern sci-fi territory, well trod from The Road Warrior to The Road. Sci-fi has always plundered more from the arts than the sciences, as witnessed by the derivation of Hollywood’s Frankenstein from Mary Shelley’s novel, published the same year as her husband’s Ozymandias.

What made the Times prefer Owen Freeman’s submerged Statue of Liberty over his underwater Grand Central? It pulls a bigger rug out from under us as an iconic symbol of America and our values, but it has another kind of potency that relates to the sacredness of the human form. Early architects believed God made man in his own image, dignifying classical architecture’s basis in the human body. Imprinted with our own form, classical architecture would no doubt retain its power for us if we learned that God looked like a duck, because the human body is also imprinted on our psyche from day one. This is why so few things disturb us as much as the visible destruction of the body, why decapitation seems more horrible than mere death. Grand Central’s classical forms may be based on the body, but the Statue of Liberty is the body. An assault on it isn’t just symbolic, but ad hominum in a way our bodies register. We identify with the peril of chin-lapping waves. Thank the personal violence of Shelley’s “trunkless legs of stone” and “shattered visage.” Never mind that the Statue of Liberty stands for the opposite of tyranny; the subversive power and romantic appeal of Shelley’s colossal ruin irresistibly fired the imagination as soon as America brought its ready-made colossus to the center of the world stage. Old Ozymandias was just rubbing his hands in the wings.

Abstracted bodies aren’t as potent as actual bodies. The next logical step therefore would be get rid of abstraction. As an architectural educator I get so tired of crit panel members telling student after student, they are being too literal. At that point I always pipe up and say abstraction is overrated, and everyone smiles, thinking I’m just being provocative for its own sake. I’m watching a documentary series on Andy Warhol right now and am lamenting that architecture never really had someone like that. Venturi was way too half hearted. We need someone who will blow taste right out of the way… I think But then, I come from prol roots.

But then, I come from prol roots.

I’ve found more if you’re curious… One more from the pre-Cold War Era. Perhaps I’ll make a second post on the subject eventually when I find a few more…

Glad you found my post interesting.