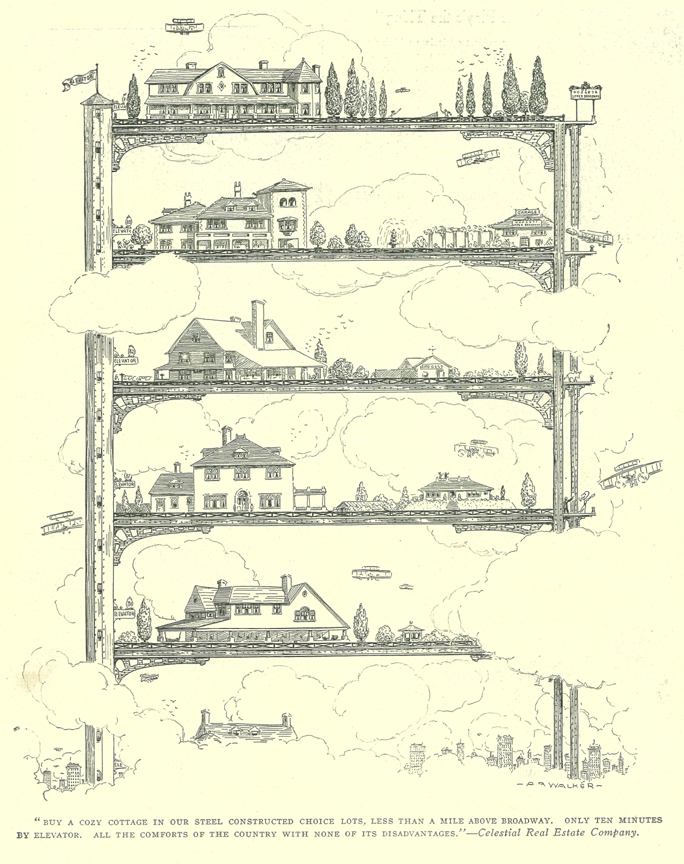

This year is the centenary of a cartoon that has had a remarkable influence on architecture. Published in Life magazine’s “Real Estate Number” of March, 1909, the full-page cartoon by A.B. Walker shows conventional houses stacked on an open skyscraper frame. Its caption reads, “‘Buy a cozy cottage in our steel constructed choice lots, less than a mile above Broadway. Only ten minutes by elevator. All the comforts of the country with none of its disadvantages.’ – Celestial Real Estate Company”

Walker’s cartoon was rediscovered by Rem Koolhaas and extensively analyzed in his seminal book, Delirious New York (Oxford, 1978, pp.69-70). Koolhaas ignored the thrust of its caption and saw in the cartoon’s picture “a theorem that describes the ideal performance of the skyscraper: a slender steel structure supports 84 horizontal planes, all the size of the original plot. Each of these artificial levels is treated as a virgin site, as if the others did not exist, to establish a strictly private realm around a single country house and its attendant facilities, stable, servants’ cottages, etc. Villas on the 84 platforms display a range of social aspiration from the rustic to the palatial; emphatic permutations of their architectural styles, variations in gardens, gazebos and so on, create at each elevator stop a different lifestyle and thus an implied ideology, all supported with complete neutrality by the rack.”

Koolhaas’s description of the cartoon’s steel frame as a “rack” points to its anticipation of Le Corbusier’s famous illustration of the concept for his Unite d’Habitation of 1947-52, as a support frame into which individual prefabricated dwellings might be inserted like bottles into a wine rack, prefiguring much of what was to follow in prefabricated architecture and other architectural streams of thought. A further link to Le Corbusier appears in the yards that surround the Life cartoon’s houses; Le Corbusier’s “immeuble villas” apartment block project of 1922 had double-height living spaces opening onto private gardens, and roof gardens were one of his “five points of architecture“.

Focusing on the cartoon’s details, Koolhaas continues, “The ‘life’ inside the building is correspondingly fractured: on level 82 a donkey shrinks back from the void, on 81 a cosmopolitan couple hails an airplane. Incidents on the floors are so brutally disjointed that they cannot conceivably be part of the same scenario. The disconnectedness of the aerial plots seemingly contradicts the fact that, together, they add up to a single building. The diagram strongly suggests even that the structure is a whole exactly to the extent that the individuality of the platforms is preserved and exploited, that its success should be measured by the degree to which the structure frames their coexistence without interfering with their destinies. The building becomes a stack of individual privacies.”

Koolhaas finds “The fact that the 1909 ‘project’ is published in the old Life, a popular magazine, and drawn by a cartoonist – while the architectural magazines of the time are still devoted to Beaux-Arts – suggests that early in the century ‘the people’ intuit the promise of the Skyscraper more profoundly than Manhattan’s architects, that there exists a subterranean collective dialogue about the new form from which the official architect is excluded.” Koolhaas had in fact been studying “sources capable of revealing unfamiliar or popular aspects of New York, like tourism brochures and postcards” in the lead-up to Delirious New York, according to Roberto Gargiani in Rem Koolhaas/OMA: The Construction of Merveilles (Routledge, 2008, p.14.)

The section-based genesis of many Koolhaas projects follows naturally on his layer-cake interpretation of buildings like the Life cartoon skyscraper and the Downtown Athletic Club in Delirious New York. Peter Eisenman (in Ten Canonical Buildings: 1950-2000, Rizzoli, 2008, p.203) sees this interpretation informing the “vertical stacking of differentiated horizontal planes that do not share a contiguity of purpose from one level to another” in Koolhaas’s 1993 Tres Grande Bibliotheque project. Laid on its side, this stratification produces in Koolhaas’s 1982 Parc de La Villette proposal what Eisenman calls “a montage of programmatic lateral bands”. Koolhaas’s “cross-programming”, such as his inclusion of performance space in New York’s Prada flagship store, or his unexecuted proposal to include hospital units for the homeless in the Seattle Public Library, follow up on his observation of the “brutally disjointed” contents of a single building in the Life cartoon.

In the 1980s, Walker’s Life cartoon inspired the “Highrise of Homes” project by James Wines and his firm SITE, a fantasy of highrise housing that would allow individual freedom and expression. As described in SITE’s Highrise of Homes publication (Rizzoli, 1982, p.41), “The two most obvious antecedents for the Highrise of Homes are the amusing 1909 drawing of a proposal for a skyscraper as a utopian device and the 1920 fantasy depicting a cooperative apartment house built according to the owners’ individual tastes. It should be noted, however, that these examples point up the difference between a casual joke and a topic of substantive research, and have been included here with hopes that a comparison of intent will work in favor of a better understanding of the Highrise of Homes.” While this statement fails to acknowledge how literally the project builds on Walker’s image, SITE’s fleshing out of his cartoon’s outlines and dense proliferation of its plantings transforms the cartoon into a different kind of art and anticipates a trend found in today’s green skyscraper proposals.

SITE credits both Walker’s 1909 cartoon and this 1920 one, also from Life, as “antecedents” for its “Highrise of Homes” project, but Walker’s image is clearly the critical inspiration and model.

More recently, the Dutch Pavilion at Expo 2000 in Hanover, Germany by MVRDV shows the influence of the Life cartoon, possibly by way of SITE’s verdant interpretation (photo: Benutzer:JuergenG). A Dutch architecture firm, MVRDV has links to the cartoon by way of Koolhaas’s firm OMA, for whom two of its principals once worked.

Last year’s proposal by architect Daniel Libeskind for a the residential Madison Square Park Tower is one of several recent highrise designs that incorporate trees in a way never dreamt of by the office ficus, and first envisioned in Walker’s Life cartoon. An emerging breed of environmentally minded skysrapers wear green on their sleeves.

UCX Architects’ Urban Cactus apartment tower, under construction in Rotterdam, may be the closest thing ever built to a realization of Walker’s concept.

Placing the cartoon in its original context of Life‘s 1909 “Real Estate Number” not only reminds us how long New York has been obsessed with this topic, but gives us a glimpse of New York’s early awareness of itself as a skyscraper city. Including the cover image, the issue’s half-dozen skyscraper cartoons all exaggerate distance from the ground. (Transportation among towers by aircraft is another of their themes, which seems to have had enough serious currency to have inspired the real-life zeppelin mooring mast atop the Empire State Building and the rooftop helipad of the Pan Am – now MetLife – Building.) What sets Walker’s houses-on-steel-frame cartoon apart from the others is its commentary on the home’s loss of immediate connection to the ground. When the first skyscrapers were rising, apartment buildings were still a recent phenomenon. As described in New York: An Illustrated History by Ric Burns, James Sanders and Lisa Ades (Knopf, 2003, p.236), “From the very start, the new structures generated controversy. One resident of the Upper East Side voiced the opinion of many prosperous New Yorkers – nearly all of whom still lived in private row houses – when he declared that ‘Gentlemen will never consent to live on mere shelves under a common roof’.”

An early apartment building, The Dakota, was designed with apartments the size of single-family row houses to entice early adopters of apartment living. Walker’s cartoon reflects on what was most fundamentally false about this promise, the lack of contact with the ground. On an entirely separate path, his image’s openness to interpretation has given it a life he could never have imagined.

I start to look forward to new posts – enjoying your thoughts and writing very much.

I agree that artistic minds – unspoiled by architectural training – have an inspirational influence on the vision for the built environment.

See the architecture of Ralph Macquarie for star wars.

Also see Ken Yeang’s work regarding garden towers.

Thank you