Once a swamp and then an ash dump, the ground of the Iron Triangle in Willets Point, Queens, now feels like both. Its businesses have an unacknowledged ancestor within one of the greatest works of American literature.

The Great Gatsby was going to be called Among Ash Heaps and Millionaires until the great Scribners editor Max Perkins persuaded F. Scott Fitzgerald otherwise. Bad as it was, Fitzgerald’s working title serves to tell how much importance he placed on the novel’s “valley of ashes,” the setting for George Wilson’s garage in the novel. The valley of ashes was based on the sprawling Corona dump which would be regraded and buried – under the 1939 World’s Fair site, now Corona Flushing Meadows Park, and Shea stadium – except for the corner of it at the tip of Willets Point that was left to its own devices and just maniacally proliferated car repair shops until it came to be known as the Iron Triangle. ArchiTakes’ search for Wilson’s Garage finds that it was almost certainly located within the Iron Triangle, a unique district whose days are numbered in the path of a city initiated development plan.

The Corona dump: “Occasionally a line of gray cars crawls along an invisible track, gives out a ghastly creak, and comes to rest, and immediately the ash-gray men swarm up with leaden spades and stir up an impenetrable cloud, which screens their obscure operations from your sight.” – The Great Gatsby

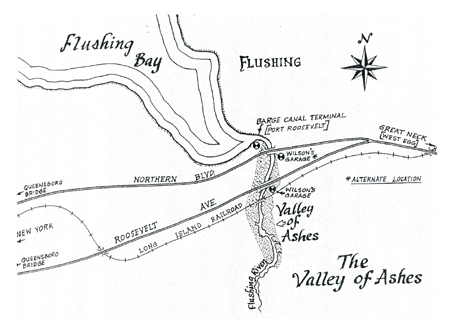

Fitzgerald moved his family from St. Paul to Great Neck, on the north shore of Long Island, in October of 1922 so he could be closer to the Broadway production of his play, The Vegetable. They stayed until May of 1924 before moving to the French Riviera in the off season, where cheaper living and fewer distractions allowed Fitzgerald to write Gatsby. His masterpiece, it was published in 1925. Fitzgerald’s experiences in Great Neck, fictionalized as “West Egg”, and Long Island’s Gold Coast provided material for the book. Trips to Manhattan during his stay in Great Neck would have taken Fitzgerald through Queens’ Corona dump, whether he rode the Long Island Railroad or drove along Northern Boulevard. (Even as he fictionalized Great Neck, Fitzgerald moved the Railroad and Northern Boulevard briefly side by side so both could pass close by George Wilson’s garage.) The dump consisted of swamp land west of the Flushing River which was being filled in with garbage, horse manure and ashes from the city’s coal burning furnaces. It provided the writer a dramatic contrast to the glamor of Manhattan and the North Shore, and resonated with his reading of T.S. Eliot’s just published 1922 poem The Waste Land.

Chapter 2 of The Great Gatsby begins:

“About half way between West Egg and New York the motor road hastily joins the railroad and runs beside it for a quarter of a mile, so as to shrink away from a certain desolate area of land. This is a valley of ashes – a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens; where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and, finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air. Occasionally a line of gray cars crawls along an invisible track, gives out a ghastly creak, and comes to rest, and immediately the ash-gray men swarm up with leaden spades and stir up an impenetrable cloud, which screens their obscure operations from your sight.

But above the gray land and the spasms of bleak dust which drift endlessly over it, you perceive, after a moment, the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg. The eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic – their retinas are one yard high. They look out of no face, but instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a non-existent nose. Evidently some wild wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sank down himself into eternal blindness, or forgot them and moved away. But his eyes, dimmed a little by many paintless days under sun and rain, brood on over the solemn dumping ground.

The valley of ashes is bounded on one side by a small foul river, and, when the drawbridge is up to let barges through, the passengers on waiting trains can stare at the dismal scene for as long as half an hour. There is always a halt there of at least a minute, and it was because of this that I first met Tom Buchanan’s mistress. . . .

I went up to New York with Tom on the train one afternoon, and when we stopped by the ashheaps he jumped to his feet and, taking hold of my elbow, literally forced me from the car. . . . I followed him over a low whitewashed railroad fence, and we walked back a hundred yards along the road under Doctor Eckleburg’s persistent stare. The only building in sight was a small block of yellow brick sitting on the edge of the waste land, a sort of compact Main Street ministering to it, and contiguous to absolutely nothing. One of the three shops it contained was for rent and another was an all-night restaurant, approached by a trail of ashes: the third was a garage – Repairs. George B. Wilson. Cars bought and sold. – I followed Tom inside.

The interior was unprosperous and bare; the only car visible was the dust-covered wreck of a Ford which crouched in a dim corner. It had occurred to me that this shadow of a garage might be a blind, and that sumptuous and romantic apartments were concealed overhead, when the proprietor himself appeared in the door of an office, wiping his hands on a piece of waste.”

Along with the obvious liberty of running the Long Island Railroad briefly next to Northern Boulevard, Fitzgerald altered the landscape in a way that hasn’t previously been noted; he flipped the “small foul” Flushing River east-for-west with the dump. This switch is the only way a Manhattan-bound train stopped for a lift bridge would find itself standing in the dump rather than the town of Flushing. While these changes take the scene two giant steps into imaginary geography, it’s easy enough to check old maps for what might have been Wilson’s Garage given a reversal of the narrative’s direction of travel from westward to eastward. A 1926 real estate map in fact shows two garages within what might be a hundred yard walk back from an eastbound train stopped at the river. They appear where 126th and 127th Streets meet Northern Boulevard. A visit to the site finds one of them demolished. What may be a more modern garage building is found in the place of the other, among older buildings that might date from Fitzgerald’s Great Neck days, almost all of which now function as garages. While this section of Northern Boulevard was more populated on the 1926 map than Fitzgerald’s “three shop Main Street,” he might have pared away his garage’s neighbors to give it a Hopperesque isolation, accompanined only by an empty store and proto-“Nighthawks” diner.

These blocks of Northern Boulevard are certainly the location of any real building that might have inspired Wilson’s garage. The presence of billboards along this stretch, possibly dating back to the time of the lift bridge, seems to confirm this. The long gone Corona dump is routinely described as Fitzgerald’s valley of ashes, but what’s been missed is the link between Wilson’s garage and the still standing Iron Triangle it pioneered. Cheap land next to a major highway would have appealed to an early garage venture, the kind of business that wouldn’t suffer from a dump-side location. What put Wilson’s garage there brought droves more until they developed into a symbiotic car repair ghetto.

A map from the 2002 book, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby: A Literary Reference, posits locations for Wilson’s Garage east of the Flushing River. Although the book was edited by preeminent Fitzgerald scholar Matthew J. Bruccoli, the map is highly unreliable. It shows the valley of ashes as a literal river valley cradling the Flushing River from either side, while the Corona dump, upon which Fitzgerald modeled his “valley”, extended only west from the river and covered a broad expanse of swampy lowland. The map also shows Roosevelt Avenue crossing the River, as it’s done only since construction of a bridge in 1928, three years after Gatsby was published. The only opportunity for a roadside garage within the dump and near the River would have been on Northern Boulevard just west of the River. A street atlas from the time of Fitzgerald’s stay in Great Neck shows two garages in this area.

Two pages of the 1926 E. Belcher Hyde street atlas of Queens show Willets Point, formed by Flushing Bay at top and the Flushing River at right. On the left-hand page, at bottom, the Long Island Railroad passes through an uninhabited stretch of dump before crossing the river in the lower right corner. At the upper right of this page, two garages are shown on Northern Boulevard, which runs along the bay’s shore. The right-hand page shifts topography slightly south. Near its bottom, the Roosevelt Avenue Bridge is shown crossing the river although it would have been still in the works. Farther up, Northern Boulevard crosses the river on the lift bridge pictured below. Most of the streets and blocks shown on these pages were only mapped and not yet built. (Today they are the blurred mud streets of the Iron Triangle.) Mostly covered by mounds of ash and garbage, Willets Point was only the extreme northeast corner of the vast dump Fitzgerald called the valley of ashes.

A detail from the left-hand atlas page above shows two buildings labeled “garage” on the south side of Northern Boulevard, the main artery between Manhattan and the North Shore of Long Island. (On the Road to West Egg was another of The Great Gatsby‘s working titles.) Fitzgerald might have idled his car outside these while waiting for the Flushing River lift bridge on a drive home from the city. Turning his head to the right as he waited for the bridge, he’d have had time to study them and their ash heap backdrop. Garages would have been rarer so early in the auto age, and the nearness of the two on this map foreshadows the district’s hyperpopulation with garages and body shops. The garage at right is centered on the northern leg of what is now the Iron Triangle. Closer to the river, it’s the most likely candidate for Wilson’s Garage.

In Flushing, Northern Boulevard was called Bridge Street after the bridge over the Flushing River. This photo shows the drawbridge of Fitzgerald’s time, which would have occasionally left eastbound drivers standing on Northern Boulevard beside the Corona dump.

Fitzgerald behind the wheel on the Riviera in 1924, when he was writing The Great Gatsby.

“. . . we walked back a hundred yards along the road under Doctor Eckleburg’s persistent stare.” A billboard at the corner of Northern Boulevard and 127th Place seems to tell the seeker of Wilson’s Garage, “you’re getting very warm.” The two-story building that raises it into view appears on the 1926 Hyde street atlas. Its upper floor suggests an above-the-shop residence and might have spurred Fitzgerald to wonder over the strangeness of domestic life on the edge of a dump: “It had occurred to me that this shadow of a garage might be a blind, and that sumptuous and romantic apartments were concealed overhead . . .” This building, like the Sunoco station just beyond it and the building in the foreground, is now a garage.

Viewed from the no man’s land under the Whitestone Expressway, the blue and white structure at right is on the corner of Northern Boulevard and 126th Street, the site of the garage nearer the river on the 1926 street atlas, and the most likely location of the inspiration for Wilson’s Garage. The trees at left conceal the billboard pictured above.

Today’s version of Wilson’s garage on Northern Boulevard, where the owner is more likely to be named Park or Kim. To its left is the blue and white building pictured above.

A study sketch by Francis Cugat for The Great Gatsby dust jacket shows the valley of ashes with balloon-like faces watching from its sky. Cugat began work on the cover while the novel was still in progress and his sketch reflects Fitzgerald’s working title, Among Ash Heaps and Millionaires. As Charles Scribner III noted in a 1991 essay, “Celestial Eyes – from Metamorphosis to Masterpiece,” Fitzgerald told his editor Max Perkins, “I’ve written it into the book.” Scribner speculates that Cugat’s floating faces inspired the billboard eyes of Doctor Eckleburg.

Francis Cugat’s painting “Celestial Eyes” may be the most famous jacket art in American literature. Cugat’s early sketches of the valley of ashes gave way to a cross between an amusement park and a city skyline, with a single more prominent floating face. His idea of eyes above the valley of ashes lives on in the novel’s text.

The historian David Trask has speculated that Doctor T.J. Eckleburg’s initials refer to Thomas Jefferson, whose vision of an agrarian republic is mocked by Eckleburg’s billboard eyes brooding over the “valley of ashes – a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens . . .” (The founding father’s initials seem a less tenuous association when the names George and Myrtle Wilson are laid over George and Martha Washington.) The Corona dump may be gone, but as debased a landscape lies beside Northern Boulevard today; not in the car-parts carnival of the Iron Triangle to the south, but in the still ashy ground under and around the Van Wyck and Whitestone Expressways to the north, created by the same Robert Moses who removed the valley of ashes. Emblematic of a national car culture, they make an even better symbol of the defilement of America’s landscape than the Corona dump. Their indifference to things human echoes the hit-and-run accident outside Wilson’s garage upon which Gatsby’s tragedy turns.

Willets point, with Shea Stadium, now replaced by Citi Field, at lower left. The Iron Triangle is at center, within the “V” formed by 126th Street at left and Willets Point Boulevard at right. Above, Northern Boulevard, now part of an extensive expressway system, completes the triangle.

Thank you so much! We had to research the Valley of Ashes for our final Great Gatsby project, including a printed map. I gave my teacher the link to this website…she agrees that you’re a genius. You’re a lifesaver!

–Nikki

Absolutely enlightening. Anyone interested in Gatsby needs to study this site!

This is a fantastic resource! I loved reading this book in school – in pre-Web days – imagining what the places looked like. I was fascinated by the map in the book! I would also imagine what it looked like today. Later, when I went to college on the East Coast and made trips to New York and the Hamptons, I would occasionally wonder if I was spotting sites from the book. So, this was a really neat treat for me!

Thank you. Great information here.

interesting. i read very little of the book in school to be honest. however being raised on long island and frequenting the boroughs i was always interested in west egg and east egg and their exact locations. there was always different opinions (great neck, manhasset, port washington, etc.) i’ve never heard of that area referred to as the iron triangle though we call it “the pit” everyone i know from queens and LI calls it that. but yes it is a network of dirt roads with huge potholes and puddles you have to drive really slow through it not to damage your car. it sits just under citi field and it’s just garage after garage tire shops mechanics everything mostly all spanish guys (papis) but due to the competition you can get anything fixed over there for a much much better price than anywhere else. from a transmission to a headlight. will not be able to pass by this anymore without thinking about gatsby.