An illustration from William A. Bruette’s 1934 book, Log Camps & Cabins, shows an example of a cabin open at one end like a cave. Outside, a campfire extends the domestic realm into nature. The composition is the barest refinement of primitive man’s cave with banked fire outside. The book’s epigraph reads: “The cabin in the forest, on the banks of a quiet lake or buried in the wilderness back of beyond, is an expression of man’s desire to escape the exactions of civilization and secure rest and seclusion by a return to the primitive.” Or in Huck Finn’s words, “The Widow Douglas she took me for her son, and allowed she would sivilize me; but it was rough living in the house all the time, considering how dismal regular and decent the widow was in all her ways; and so when I couldn’t stand it no longer I lit out. I got into my old rags and my sugar-hogshead again, and was free and satisfied.” Few humans would prefer any kind of architecture to the pleasure and freedom of being outdoors in comfortable weather. Even without retreating “back of beyond,” houses can make the most of their devil’s bargain between shelter and space.

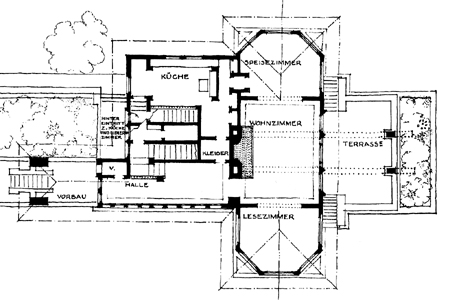

The plan of Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1901 Henderson House is a near mirror-image of his Hickox House of 1900 (see House Rule 2) and very similar to his proposal for “A Home in a Prairie Town,” published in the Ladies Home Journal in 1901. Each of these combines living functions into a single long but articulated space; dining area and library on either side of a living room with hearth. In each house, the living room spills out onto a terrace that matches its width and axial relationship to the hearth; living room and terrace can be read as a single space incidentally divided by French doors. In the drawing above, the living room’s ceiling beams – shown in dashed lines – extend through the exterior wall and over the open terrace, further claiming its outdoor space as an extension of the interior.

Wright’s 1905 Darwin Martin House Complex weaves together indoor and outdoor space. The main house is a more complex development of the Hickox and Henderson House plans Wright had earlier seen fit to repeat. Their terraces are here replaced by a covered porch, the floor of which is finished in the same one-inch square floor tiles as the living area. Above and below, the porch is a more committed relationship of interior to exterior. A crescent of planting gives the porch privacy and defines an extended domain for the established grouping of library, living and dining room.

The enclosed space of Mies van der Rohe’s 1929 Barcelona Pavilion projects itself into open air by the suggestive effects of continuous flooring, interpenetrating walls and an overhanging roof. Mies acknowledged Wright’s impact from the time of the 1910 German Wasmuth Portfolio of his work.

Graham Phillips’ 2001 Skywood House adapts the exterior-claiming strategies of the Barcelona Pavilion to a home. Pushing the limits of minimalism, it comes full circle to the image of a cave facing a clearing.

A drawing detail of Sir Edward Brantwood Maufe’s 1912 Kelling Hall shows a wing ending in a concave wall that seems to draw in outdoor space. Maufe reverses the usual projecting bow-window in favor of an implied exterior room, blurring the transition from enclosed interior space to nature. The primitive cave and its threshold are refined into a cut-stone concavity and terrace.

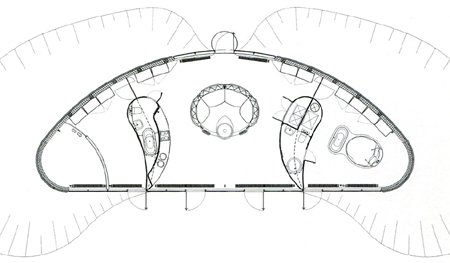

Future Systems’ cave-like 1998 House in Wales is bermed into the ground at the top of a cliff. It looks out over the sea through an elliptical wall of glass, like an eye. Describing it, Jan Kaplicky of Future Systems said: “There is only the grass and the glass. Nothing else, no architecture.”

The floor plan of the House in Wales shows earth mounded up on either side and around the back, except for a narrow gap for the main entry door, centered on the curved rear wall. The earth falls away more broadly at the straight section of wall, which is entirely glass where exposed, allowing an expansive view over the sea. At the center of the house, a curved sofa focuses on a suspended fireplace, re-enacting the campfire circle of our cave-dwelling forebears and heightening the design’s contrast of primitive to futuristic. Symmetrical teardrop-shaped cores contain bathrooms, utilities and the kitchen counter. Their shape creates both a fluid transition between rooms and a sense of space expanding into nature. The curved back wall embraces the vista, drawing the outdoors into the greater circle it implies. Without any exterior effort to claim outdoor space, the house is made entirely one with it, and infinitely amplified.

Tezuka Architects’ 2005 Floating Roof House has banks of sliding doors on either side. When they are fully retracted, the interior becomes an open-air pavilion protected only by a narrow roof. Rather than spilling out to the exterior, the interior is itself transformed into outdoors. The strategy, a hallmark of Tezuka’s work, was pioneered by Mies van der Rohe in his 1930 Tugendhat House, with its glazed living room wall that disappears down a slot into the basement.

Barton Myers’ 1999 House and Studio at Toro Canyon makes interior convertible to exterior with walls of glazed garage doors. The house is a high-design response to the impulse of American suburbanites who in warm weather relax on lawn chairs in their garages, the door drawn up overhead, sipping beer from cans and paying unconscious homage to the threshold-dwelling ambivalence of our caveman forebears.

Rule 5 is to engage the outdoors.

Conceive of the living space of a house as part of a greater whole that includes exterior space. Minimize the barrier between the indoor and outdoor components of this whole and unite them with a common material, breadth or boundary, or by inflecting the inside of the house to address its surroundings. The interior will gain a sense of release, its perceived boundary expanding into the outdoors.