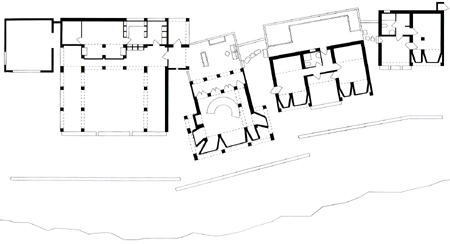

Architect Jørn Utzon’s home, Can Lis, was completed in 1972. Composed of individual structures and courtyards, it stands on a cliff overlooking the sea in Majorca, Spain. A one-room building at its center contains a built-in crescent seat facing the vista through deep openings, with a fireplace on one side.

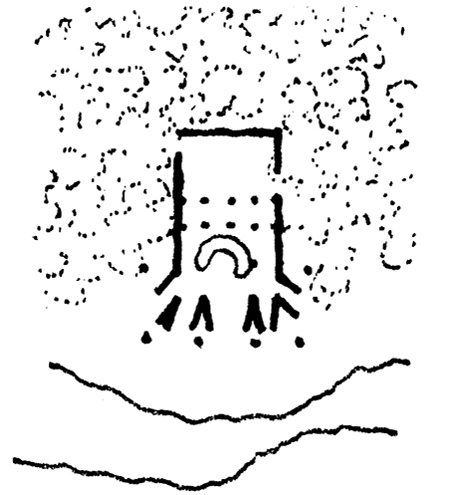

A primitive sketch by Utzon shows the house’s central pavilion and its curved seat in isolation, suggesting they were the germ of the entire house.

Can Lis was partly inspired by a cave Utzon found on the site, which informs the house’s site-quarried stone walls and tunneled windows, their concealed frames suggesting unglazed openings. The central structure’s seating evokes a campfire circle, adding to the primal appeal. A vision of relaxed family and friends enjoying each other and the scene would have made human experience the starting point of the house’s design. As Thoreau wrote in Walden: “What of architectural beauty I now see, I know has gradually grown from within outward, out of the necessities and character of the indweller, who is the only builder, – out of some unconscious truthfulness, and nobleness, without ever a thought for the appearance; and whatever additional beauty of this kind is destined to be produced will be preceded by a like unconscious beauty of life.” Utzon’s centerpiece recalls the more succinct Thoreau who asked, “What is a house but a seat?” Most people admit to spending the majority of their waking hours at home in one or two pieces of furniture. Given the favorite chair’s outsized role as life’s cockpit, the selection and arrangement of furniture warrants primary consideration in the design of a house.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1939 Goetsch-Winckler House is typical of his Usonian houses in its use of built-in furniture, here including a fireplace seat, two tables, a bar, a desk and bookcases. Only the central living room furniture is left to the owner’s discretion. Integrating furniture from the house’s conception, Wright unified the immediate accommodation and experience of the dweller to the overall dwelling. The built-in furniture also makes efficient use of space, allowing a compact house to generously serve multiple functions, and gave Wright a high level of control; for costlier houses he might design all of the furnishings down to the napkin rings. Wright once visited Graycliff, the summer house he had designed for Darwin D. Martin and his wife Isabelle, shortly after its completion. Finding no one at home, he let himself in and discovered that furniture had been moved from the locations he had laid out. The Martins later returned to find it pushed back into Wright’s preferred arrangement, and fresh flowers on the dining table. The story doesn’t just portray Wright’s ego; it tells how fully he viewed furniture as an integral part of his architecture.

Furniture as architecture: using raw space as a backdrop, a Design Within Reach catalogue photo demonstrates the power of furniture alone to create a domestic sphere and set a tone. Animating even an unoccupied room, it suggests human presence, social interaction and lifestyle. (Eero Saarinen’s 1948 Womb Chair, at right in the photo, was designed in response to a request by Florence Knoll’s for “a chair she could curl up in.”) A huge share of classic twentieth century furniture, more popular now than ever, was designed by architects like Saarinen, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer, Charles and Ray Eames, and Arne Jacobsen.

In place of traditional partitioned rooms, furniture groupings define various living functions in Philip Johnson’s Glass House. Johnson’s use of furniture designed by Mies van der Rohe acknowledges the inspiration of his Farnsworth House. Mies pioneered not only the glass house, but the use of furniture to mark different activity areas within open and flexible space. The Barcelona Chair Johnson incorporated was designed by Mies for his German Pavilion at the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, as seating for the King and Queen of Spain to oversee opening ceremonies. Created for a specific couple and building, the chair has long since become a lumbar-oblivious cliché of corporate lobbies. It’s thought to be inspired by folding curule seats used by Roman aristocracy, an appropriate provenance. Mies also made the chair extra wide, turning the height of a throne on its side to suit both traditional prestige and the radically modern horizontality of his pavilion. A bridge between body and building, the Barcelona Chair is a quintessential reminder that furniture is architecture.

Rule 6 is to incorporate furniture.

Design for furniture. A house might be said to consist of furniture groupings and the paths among them. Base the size, shape and orientation of spaces on optimal furniture arrangements, especially as they relate to light, views and circulation paths. The final assessment of a house is made from the vantage of its sofas and chairs. Starting with the view from these will insure a satisfying end. Furniture itself is architecture, and its design has as much bearing on quality of space as do walls and finishes. Include its cost in the budget for a house and, before scrimping, weigh its impact against other costs. Consider that a person can be only one place at a time, and will spend the great majority of time in one or two preferred seats. Match furniture to the character of its users and setting.