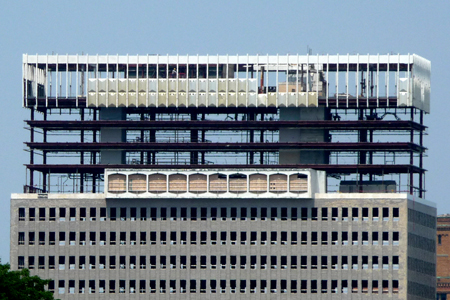

Photographed last week, Midtown Plaza’s piecemeal demolition brings the look of a ship breaking yard to the skyline of Rochester, New York. The image may be bracing to those who remember the project’s promise of urban renewal when it was completed in 1962, to the design of urban planner Victor Gruen. According to the Wikipedia entry on Midtown, “Gruen was at the height of his influence when Midtown was completed and the project attracted international attention, including a nationally televised feature report on NBC-TV’s Huntley-Brinkley newscast the night of its opening in April 1962. City officials and planners from around the globe came to see Gruen’s solution to the mid-century urban crisis. Midtown won several design awards.”

A Jewish refugee from Nazi occupied Vienna, Gruen said he arrived in America with “an architectural degree, eight dollars, and no English.” He went from designing Fifth Avenue boutiques to a role as one of America’s premier urban planners. Melding his insights into consumer psychology with a conviction that retail spaces could create communities, Gruen invented the shopping mall. He strove to bring the urbanity of his native Vienna and Europe to America, claiming the Milan Galleria was his model for the mall. In 2004, Malcolm Gladwell wrote in The New Yorker that “Victor Gruen may well have been the most influential architect of the twentieth century” for his creation of the pervasive archetype. Gruen’s impact continues to be registered. Gladwell’s appraisal followed on the publication of Jeffrey Hardwick’s 2004 book, Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream. A decade ago, the media theorist and concept-coiner Douglas Rushkoff began popularizing the Gruen Transfer, also known as the Gruen Effect, by which shoppers are intentionally disoriented and distracted by the retail environment, so they’ll lose focus and succumb to impulse buying. Since 2008, The Gruen Transfer has been the title of an Australian TV series on advertising. In 2009, Anette Baldauf and Katharina Weingartner released the documentary, The Gruen Effect: Victor Gruen and the Shopping Mall.

Midtown Plaza introduced the nation’s first urban shopping mall, within a mixed-use megastructure. The project included 2,000 underground parking spaces, a 300-seat auditorium, and an office block with a hotel above (here shown disappearing). A restaurant projected from the base of the hotel element, providing dramatic views from what was Rochester’s tallest building. Two skyways connected the complex to nearby office buildings. Gruen wrote, “It is our belief that there is much need for actual shopping centers – market places that are also centers of community and cultural activity.” In its coverage of Midtown Plaza, Architectural Forum magazine quoted Gruen as saying, “We wanted to create a town square with urbane qualities. At the same time, the Plaza is important as a setting for cultural and social events – concerts, fashion shows, balls, and those activities which one connects with urban life.” Gruen’s formula for urban renewal included a downtown mall, ample parking, and a ring road to ease car access to parking. The ring road was adopted from his native Vienna. Gruen found one ready made in Rochester, whose residents may be stunned to learn that someone once saw Vienna’s Ringstrasse in their unassuming Inner Loop.

Despite its importance as an artifact of American urban planning, Midtown isn’t the sort of project that gets preserved. The recent Cronocaos exhibition organized by Rem Koolhaas and his OMA partner Shohei Shigematsu, accused preservationists of scenographically cherry picking what to preserve and whitewashing urban evolution. In his review of the show for the New York Times, Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote, “This phenomenon is coupled with another disturbing trend: the selective demolition of the most socially ambitious architecture of the 1960s and ’70s — the last period when architects were able to do large-scale public work. That style has been condemned as a monstrous expression of Modernism.” Examples noted in the show included East Berlin’s Palast der Republik and Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower. Koolhaas’ own respect for ambitious mega-projects would seem sympathetic to Midtown Plaza, if malls weren’t the essence of the air-conditioned and escalatored nowhere he’s named “Junkspace.”

In his 1964 book, The Heart of Our Cities: The Urban Crisis, Diagnosis and Cure, Gruen prominently featured Midtown Plaza, documenting its advertised social role with this newspaper photo of a high school dance on the floor of its shopping mall. Helped by a tailwind from the 1960s economic boom, Midtown was initially an undeniable success. Within twenty years, it proved to have been a mere eddy against the inexorable tide of white flight and sprawl fueled by the more common suburban version of the mall.

Writing in the 2002 book, The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping, contributor Sze Tsung Leong writes: “Victor Gruen, widely acknowledged as the inventor of the shopping mall, was, in the end, not interested in shopping. Instead, the shopping mall was a vehicle toward his real ambition: to redefine the contemporary city. For Gruen, the mall was the new city.” Leong quotes Gruen’s 1960 book, Shopping Towns USA: “By affording opportunities for social life and recreation in a protected pedestrian environment, by incorporating civic and educational facilities, shopping centers can fill an existing void. They can provide the needed place and opportunity for participation in modern community life that the ancient Greek Agora, the Medieval Market Place and our Town Squares provided in the past.” Leong observes, “At he same time that Victor Gruen was configuring the mall to provide civic functions, he was also envisioning the suburban shopping mall as a model for downtown revitalization.” Midtown Plaza would be the first implementation of this vision. Although the shopping mall would indeed serve a social role, particularly among teenagers, the idea that it would be the new Agora now ranks with early hopes that TV would be educational.

Banking on a single project to revitalize a city might seem quaint but for the recent example of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which so successfully jump-started the Basque town’s economy as to give urbanism the Bilbao Effect. (Photo: User:MykReeve.) Gehry worked for Victor Gruen in the 1950s when Midtown Plaza was being designed and is said to have been greatly influenced by his views on city planning. It was during this time that Gehry changed his name from Goldberg as Gruen had changed his own from Grünbaum, immigrants self-inventing in American Gatz-to-Gatsby fashion. Early in his own practice, Gehry used his experience in Gruen’s office to design several shopping malls including Santa Monica Place. In Bilbao, Gehry’s building inverts Gruen’s urban mall strategy, making culture a vehicle for commerce. The commercialization of museums has been much commented on, as their shops take up increasing amounts of space and multiple locations within, while sprouting external outposts with no museum attached at all.

The 2001 Prada flagship store is the design of OMA, the architecture firm of Rem Koolhaas, another contributor to The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping. The design seems to respond particularly to a post-Gruen world where shopping has been established as the answer to everything. According to OMA’s website, the design is part of the firm’s “ongoing research into shopping, arguably the last remaining form of public activity. . . . As museums, libraries, airports, hospitals, and schools become increasingly indistinguishable from shopping centres, their adoption of retail for survival has unleashed an enormous wave of commercial entrapment that has transformed museum-goers, researchers, travelers, patients, and students into customers. The result is a deadening loss of variety. What were once distinct activities no longer retain the uniqueness that gave them richness. What if the equation were reversed, so that customers were no longer identified as consumers, but recognized as researchers, students, patients, museum-goers? What if the shopping experience were not one of impoverishment, but of enrichment?” The Prada store’s response is its dual-purpose central wave. OMA’s website explains how it works: “On one side, the slope has steps – ostensibly for displaying shoes and accessories – that can be used as a seating area, facing a stage that unfolds from the other side of the wave. The store thus becomes a venue for film screenings, performances, and lectures.” An impressive amount of valuable retail space was dedicated to this conceit, which appears mainly to justify the Koolhaas trademark of blended floor levels. Asked about the frequency of the stage’s use, the store’s management referred the question to Prada’s corporate office which referred it in turn to its public relations department, approachable only by fax, and so far unresponsive. Victor Gruen had ruefully learned decades earlier that when push comes to shove between commerce and culture, commerce wins. Prada’s entire SoHo setting has itself lost most of its distinctive urban character in its transition to an outdoor shopping mall dominated by national chains.

Victor Gruen ultimately regretted the impact of the mall archetype he had created. According to Jeffrey Hardwick’s Mall Maker, in a 1978 London speech he criticized Americans for perverting his ideas, saying “I refuse to pay alimony for those bastard developments.” Hardwick writes that at seventy-five, “Gruen had reached the end of his faith in the power of architectural solutions,” continuing that “In Gruen’s opinion, the shopping center had become focused solely on its primary goal of promoting retail and had abandoned its possible role in creating new communities.” His suburban malls had not only failed to bear civic fruit, but had helped kill the city itself, while putting the American car culture he despised on steroids. Mall Maker quotes one of Gruen’s business partners, Karl Van Leuven, describing an early 1950s visit with Gruen to the site of their gigantic Northland mall outside Detroit: “‘There were all those monstrous earth moving machines pushing and shoving and changing the face of some 200 acres,’ he recalled. After watching this impressive effort, Gruen turned to Van Leuven and softly said, ‘My God but we’ve got a lot of nerve.'” Given the greater impact, on Detroit and the American city and landscape, Oppenheimer’s “destroyer of worlds” moment comes to mind. The genie was out of the bottle.

In a 1994 essay, “What Ever Happened to Urbanism?” Rem Koolhaas described an out of control urbanism that will be replaced by “an ideology: to accept what exists. We were making sand castles. Now we swim in the sea that swept them away.” Many see only resignation in his stance, but old-school urbanism can be seen washing away this month on the Rochester skyline.

Wonderful article! To your key fact that Gehry once worked for Gruen, I can add the trivial fact that Louis Kahn’s First Unitarian Church in Rochester, was for a congregation whose old church had stood on the site of Midtown Plaza. It was from their compulsory acquisition payout, that Kahn’s church was built. Further trivia: that congregation’s leader c.1900, was Dr. William Gannet, one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s early mentors. Given their connection to Wright, the congregation were pushing Kahn for a dumb-bell plan building, like Wright’s Unity Temple, which is kinda why they got a doughnut shaped building. Kahn weren’t about to play second fiddle, especially since he was their second choice. They asked Wright first to design it. And look, I found a free to download article on the whole horrible tale

http://ogma.newcastle.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/uon:3921?exact=subject%3A%22Unity+Temple+%28Oak+Park%2C+IL%29%22

But again, your article is far more interesting. I really should read more Koolhaas I think! Or better still, read him through you.

After reading this entry I ordered the “AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington” so I that I can learn more about my home town.